“VT is not TV”: Early Video Art, Television, and the Politics of Broadcasting by Kara Carmack

EAI posted an open call for essays in response to the original Open Circuits conference, and provided access to archival materials to the three selected writers to support their engagement with this history. This second essay, by art historian and curator Kara Carmack, addresses the inception of Manhattan public access television in July, 1971. Drawing from an array of foundational public access specials ranging from activist content, to artistic experiments with live broadcast, and hobbyist dispatches, Carmack offers community access television (CATV) as an essential lens through which to frame the governmental interests, local politics, and artistic experiments from which early video art emerged.

In the year since this essay was first commissioned, the United States has seen significant shifts in our media landscape—including the federal defunding of National Public Radio (NPR) and Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Carmack’s essay sheds light on the historic tension between public access channels and the governments which steward them; the use of public media broadcasting as a platform for open political discourse and dissent; and the role of artists in activating this powerful tool, with or without robust financial resources.

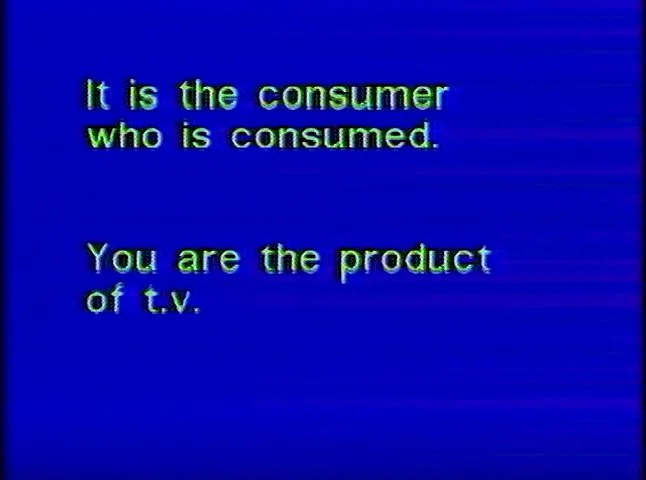

Richard Serra and Carlotta Schoolman, Television Delivers People (1973).

Manhattan public access television remains a lesser-known aspect of New York City’s art historical narrative. Despite limited access to the medium in its debut year of 1971, the city’s public access channels were central to New York’s creative classes from the 1970s through the early 90s—a period that coincides with the rise of video art and institutional critique. At the time, artists across the U.S. were experimenting with new recording and broadcasting technologies and sought to infiltrate the airwaves. Early examples include artist-video programs developed for San Francisco’s KQED and Boston’s WGBH-TV, and singular interventions like Chris Burden’s TV Hijack (February 9, 1972), and Richard Serra and Carlotta Schoolman’s Television Delivers People (1973). That Howard Wise founded Electronic Arts Intermix and Steina and Woody Vasulka established The Kitchen downtown the same year the city launched its public access channels testifies to the significant correspondence between video art’s early institutionalization and artists’ unprecedented access to television broadcast technology. Turning our attention to the form and function of community access television (CATV) and its broad spectrum of programming—from the amateur to the esoteric—supports an expanded view of video art’s production and distribution in the medium’s nascent years, and offers an important lens through which to read our contemporary digital landscape of user-generated videos on platforms such as YouTube, TikTok, and Twitch.

Until New York City mandated cable companies to set aside channels for public use, the airwaves remained under the exclusive control of large media corporations. The launch of Manhattan’s public access channels on July 1, 1971, meant a new means of communication beyond the regulations imposed by network television’s corporate directors, sponsors, and producers, serving a much-needed pluralistic and community-empowered corrective to the capitalist, nationalist, and neo-imperialist underpinnings of the sprawling telecommunication systems. Glenn O’Brien, creator of the punk variety and talk show TV Party (1978-82) underscored the necessity for local origination programming:

NEW YORK is America’s greatest center of culture, but this culture is nearly totally blacked out of radio and television communication. New York has dozens of the greatest bands in modern music but their music is not played on the radio. New York performers are not seen on television. Why should we import all of this “talent” so inferior to our own? We are not doing it. It’s being beamed in. The Networks are polluting our environment.¹

To participate in CATV was to engage in the hyperlocal politics of media production and consumption, broadcast technology, and artmaking and distribution.

Douglas Davis, The Last Nine Minutes (1977), from Documenta 6 Satellite Telecast (1977) with Joseph Beuys, Douglas Davis, and Nam June Paik.

Artist and critic Douglas Davis saw exciting promise in the new platform: “a dollar devoted to [cable], this exceedingly low-cost and time-rich medium, will produce many more hours of actual experiment (in terms of broadcasting) than a dollar flushed down the hideously expensive drain that is networks—and PBS, now itself a big business."⁴ Indeed, visitors could soon tune in to discover an eclectic and unpredictable assortment of programs that included late-night puppet shows, non-English programming for immigrant communities, amateur variety shows, health advice, concerts featuring local bands, school board meetings, televangelist sermons, government hearings, local news reports, activist programs, and late-late-night sex shows.

But to make public access shows and to watch them in the early years was not as straightforward nor as democratic as the city’s franchise agreement may have intended and as artists and activists had hoped. Higher income neighborhoods were the first to receive cable access television and it would be years before it penetrated lower-income neighborhoods across the borough. At the beginning of 1973, only approximately 110,000 were wired for cable of Manhattan’s 630,000 households.⁵ Even artists, who were courted by the cable companies to create programming for their nascent channels, struggled to fully participate. A 1973 editorial in the Soho Weekly News observed that the wiring of SoHo, a neighborhood at the city’s center of artistic experimentation, “seems to be of the lowest priority.” “This is not fair to the artists who are creating,” it argued, “nor to the community which wishes to participate.”⁶

Manhattan Cable TV “Manhattan Eyes” animation on Channel J (ca. mid-1980s).

Artist and public access producer Liza Béar further summarized the significant obstacles both producers and viewers faced: “minimal financing (no ratings no sponsors), unreliable transmission, scant listings, and snide remarks or the total indifference of most mass media journalists who prefer to, or are encouraged by their editors or the owners of the publication to focus on the tiny percentage of porn shows (4 out of 200 producers) at the expense of three years’ worth of genuine experimental work.”⁷ Other barriers included access to equipment and the technical knowledge to operate and produce programs. Though half-inch video tape cameras were more affordable and portable than studio equipment, they remained outside the reach of many. Cable providers lent broadcasting technology to the public for free on a first-come, first-served basis, but this equipment was in limited supply and often outdated.

Responding to the gap in public access’s self-described democratic nature and its actual accessibility, organizations like Theodora Sklover’s Open Channel, Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) at Automation House, and New York University’s Alternate Media Center opened studios to provide equipment and training to local individuals and groups to support new content production (following in the vein of media activists like Michael Shamberg and the publishers of Radical Software). Cable companies and neighborhood organizations set up viewing centers around the city for those who lived in neighborhoods not yet wired for cable or for those who couldn’t afford the $6 monthly subscription fee. Such efforts attempted to bridge the huge socio-economic and cultural gaps in knowledge, technology, and access to an otherwise tightly controlled, regulated, and exclusionary medium.

Despite CATV’s technical and logistical limitations and challenges, artists embraced the opportunity to cablecast their work to both art and non-art audiences beyond the walls of galleries, theaters, and museums. Some artists’ series platformed tapes and films that were being shown in other venues across the city. E.A.T.’s anthology series Artists and Television included films and videos by Michel Auder, Joan Jonas, Lucas Samaras, Michael Snow, and Keith Sonnier, and The Film-Makers’ Cooperative produced a program that featured filmmakers sharing and talking about their work. Individual videos by Douglas Davis, Nancy Graves, and Les Levine appeared alongside and sometimes as part of serialized shows, such as Paul Tschinkel’s Inner-Tube (1979-84); Coca Crystal’s If I Can’t Dance, You Can Keep Your Revolution (1977-95); Colab’s numerous public access endeavors like Potato Wolf (1979-84); Jaime Davidovich’s The Live! Show (1979-84); Willoughby Sharp and Liza Béar’s Communications Update/Cast Iron TV (1979-1991); and Jeff Turtletaub’s The Wild Wild World of Jeff Turtletaub (1979-82); among countless others.

This alternative mode of viewership meant viewers could drop-in on programming enmeshed within the incessant flow of television in a variety of environments: at loft parties, in bars and restaurants, domestic settings, and hotels. Anton Perich, public access pioneer and creator of the soap-opera parody Anton Perich Presents (1972-ca. 1978), railed against what he saw as the bourgeois art world establishment in the Daily News: “I think it is good but wrong. How many people can be in theaters? Here in the loft you see almost 50 people sitting around seeing my tapes last night. Videotape is made for watching in the home, for television.”⁸ Turning the knob on their sets in search of Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show or The Mary Tyler Moore Show, subscribers could stumble upon artist videos, performance art, avant-garde music, and other groundbreaking developments without—for better or worse—any preconceived knowledge or context.

Jaime Davidovich, The Live! Show Promo (1982).

CATV had largely lost its relevance by the 1990s as the naïve optimism of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s for a telecommunications revolution faded. However, the advent of the internet in the 1990s opened new avenues for creative and networked modes of communication built upon the groundwork of public access channels. Consider the parallels between vloggers like Shay Carl who document their lives for public consumption, and Colab’s Sally White and Mitch Corber’s real wedding-turned-experimental video broadcast in 1984. Petra Cortright toying with digital tools in VVEBCAM (2007) finds correspondence with Jean-Michel Basquiat’s experiments with the television studio’s character generator during live broadcasts of Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party. The two-way communication between Twitch streamers and chat and Coca Crystal’s live call-in segments invites affective, social exchanges through their respective media. Addie Wagenknecht’s YouTube makeup tutorials that unexpectedly shift into internet literacy lessons have important precedent in CATV media activist programs, like Martha Rosler’s reading Vogue on Paper Tiger Television (1982). Absurdist humor and performances link alantutorial’s Youtube video How to Crush a Can of Dr. Pepper with Slats of Wood (2012) with Stefan Eins’s experiments in Making Coincidences (1984).

In 1975, Ann Arlen observed in Radical Software that “the concept of regular people being able to appear on television in an everyday way, and talk to other people who make up a viewing audience, is so alien to us in this land of experts.”⁹ Fifty years later, following years of algorithmic optimization, the professionalization of the influencer, and unchecked consumerism of the internet era, some of the most-watched content is now made by “regular people.” Thus, to turn our gaze to CATV in the 1970s and 80s is to not only expand discourses on video art, performance, media activism, and broadcasting, but to also historicize the media landscape we find ourselves immersed in today.

Kara Carmack is an art historian and curator who specializes in modern and contemporary art and visual culture with an emphasis on creative communities, gender and sexuality, and archives. She received her PhD in art history from the University of Texas at Austin and has previously served as the Assistant Director of Exhibitions and Public Programs at the New York Studio School; Assistant Professor of Art History at Misericordia University; and head of the Ad Reinhardt catalogue raisonné project.

Her current book project, Marginal Centers: Parties on, off, and through Manhattan Public Access Television, 1972-1983, focuses on public access television shows produced by Anton Perich, Glenn O’Brien, and Andy Warhol. Her research has been supported by the American Association of University Women and the Association of Historians of American Art. She has contributed to numerous publications, including the Journal of Visual Culture, Burlington Contemporary, the edited anthology Pop Cinema, and various exhibition catalogues and brochures.

This essay was published with support from the Terra Foundation for American Art as a part of Video After Television: Open Circuits Revisited.

Notes

Glenn O’Brien, “T.V. Party Manifesto,” East Village Eye, Summer 1980, 29, 18.

See Gwen Allen and Cherise Smith, “Thematic Investigation: Alternative Modes of Distribution,” special issue, Art Journal vol. 66, no. 1 (Spring 2007); Gwen Allen, Artists’ Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011); and Julie Ault, Alternative Art New York, 1965-1985 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003).

Douglas Davis, “The Decline and Fall of Pop,” in Artculture: Essays on the Postmodernism (New York: Harper and Row, 1977), 86.

“Editorial: Underground,” Soho Weekly News, November 15, 1973, 2.

John J. O’Connor, “‘Permissiveness’ linked to audience size,” The New York Times, January 19, 1973, 67.

Liza Béar, “All Aboard! A survey of incentives and impediments to public channel usage by New York artists and fellow travelers,” The Independent (March 1983), 12.

Ernest Leogrande, “Fit to Be Taped?,” Daily News, February 27, 1973, 6.

Ann Arlen, “Public Access: The Second Coming of Television?,” Radical Software vol.1, issue 5 (1975), 82.