Oral History: Philip Mallory Jones (Part #3)

This is the final chapter of a three-part conversation with media artist Philip Mallory Jones. Having worked with video technology for over five decades, Jones has carved out an expansive and idiosyncratic body of work that has ranged from impressionistic portraits of Black American life to experimental works made in Burkina Faso and Angola and explorations of digital technologies such as the optical disc and the virtual environment Second Life. He co-founded and directed Ithaca Video Projects (1971-1984), an influential media arts center, and its accompanying annual video festival, one of the first of its kind. His recent work has focused on using 3D modeling software to reconstruct Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood circa 1940.

This third section of the oral history, facilitated by EAI’s Communications and Special Projects Associate Tyler Maxin, covers Jones’ experiences in live theatrical video projection, his engagement with video games, his collaborations with his mother, Dorothy Mallory Jones, and brother, Donald Brooks Jones, experiments in VR, and more. It has been edited for content and clarity.

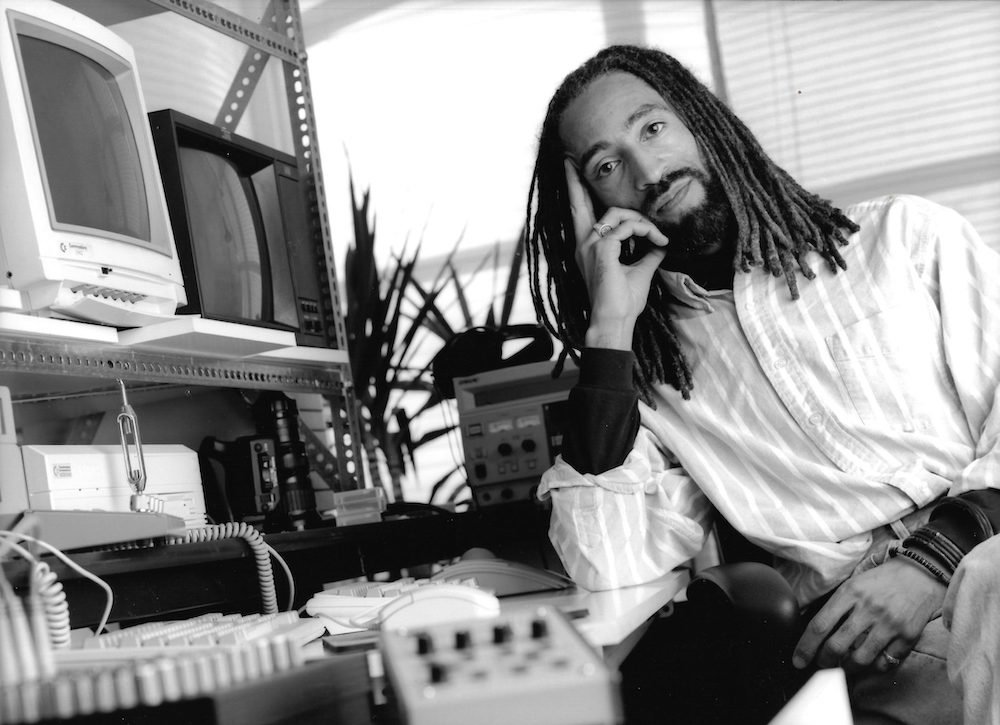

Image: Portrait of Philip Mallory Jones in front of his workstation, Mesa, Arizona, 1996. Photo by Katherine Milton, Ph. D.

Tyler Maxin: You have a varied history of working collaboratively. Could you talk about some of these projects? To start, you have considerable experience working in live theatrical productions, devising immersive video backdrops.

Philip Mallory Jones: The first was Jones, Hammons and Jones, which was performed at Just Above Midtown (JAM) in 1983 with Bill T. Jones and David Hammons. It was a really interesting, challenging, surprising experience for me to go into this with these legends and make something out of thin air. We got our initial guidance from Bill T.'s current interests. He had several themes and situations in mind that he was working on with his dancers—there were two dancers in the piece, aside from himself.

David and I worked off of that initial core, using it to shape our work and give it a place, duration, and expanded visual and narrative elements. We had three performances at JAM, each one of them different. The best performance was the second night. Two friends of mine from Ithaca, Ann Michel and Philip Wilde, showed up at this performance, unannounced to me. These were media people that I'd been working with for years and knew quite well. The second scene of the performance—the transition from the first scene to the second scene—was very difficult for me because it involved a complete reconfiguration of 10 or 15 black-and-white portable displays.

We were working with CRTs then and 12 or 15 little surveillance black-and-white cameras. I had figured out this arrangement where all the monitors were stacked in a pyramid shape on a platform at the rear of the performance area, and each of the monitors showed a different view of the set. The cameras were set up so that at a certain moment of this scene the performers would hit a certain spot, which had its own camera to document that particular moment and perspective. What the audience is seeing—aside from the live performance of the piece—is this kind of fly's eye view of the stage, displayed on this pyramid of monitors behind them.

You get a composite montage in the background with the live performance in front of it. We had to change from the first scene, in which the monitors sat on the floor in a line, all showing waves in and out and the sound of surf—a beach scene. I had to change from that to setting up and moving all the monitors, all between scenes. The first and third night, it was a bit raggedy, but that night with Ann and Philip there, it was set up so fast that there was a lag time between when the performers were to come out again.

So in those several minutes, the audience is looking around and talking, and the stage is quiet. All of the sudden, David is moving around the space as if he were a janitor. He's got a rag in his hand, moving really slow, just wiping table tops and wiping off this and that, doing this kind of shuffle, not paying attention to anybody. There came a point where the whole audience recognized, “Oh, there's another performance happening here.”

Image: Bill T. Jones, Philip Mallory Jones, and David Hammons at Just Above Midtown/Downtown Gallery (JAM), 1983. Photograph by Dawoud Bey.

Another live stage piece that I was involved with was called Drumming with Tania Léon, a Cubana composer and musician interested in percussion traditions, and Bebe Miller, a choreographer and dancer. The three of us were put together to make a piece, which happened at the Lincoln Theater in South Beach, Miami. This was the late nineties. We did a series of jam sessions around the Miami area with seven different percussion traditions: Cuban, of course, West Indian, Peruvian, Native American, Japanese, African American jazz, and Korean.

Every month or so for several months, we would stage a jam session somewhere around the Miami area organized by Miami Light, Inc. in order for Tania to collect rhythms, Bebe to collect movement ideas, and for me to capture video and sound of these jam sessions. All of this was sifted and refined, and ended up as a stage performance called Drumming with Tania directing and composing for a group of Miami Symphony musicians—actual percussionists from these various traditions on stage at various times—and Bebe dancing and interpreting these movement traditions. And there was projection by me, a lot of it animated and highly post-produced, as well as audience footage from these jams.

Another real-time live stage collaboration was with Lenwood Sloan, who wrote and directed the Vo-Du Macbeth (2001). My involvement with that project went on for over 10 years, through all the workshops and experiments that went into developing that piece. The play took Shakespeare's idea and basic narrative, and placed it in 1863 New Orleans amongst the Creole elite. What I learned about Creole culture, tradition, and community was very exciting. I mean, these people owned property. These people were the blood relatives of the New Orleans white aristocracy. They inherited, along with the white heirs of the New Orleans aristocracy. They had a standing militia of their own. They had their own mayor for Tremé, their city inside New Orleans.

One of the most interesting things about the whole project was coming to understand the Creole worldview. Because at the conclusion of the Civil War, the Northern Yankee English speaking Protestants took over, right? New Orleans was based on the Napoleonic codes. These people spoke French. They looked to Paris as the capital, not Washington D.C. When the Yankees came in, these English-speaking Protestants told them that now you are either Black or white. This was entirely foreign to the Creole elite, that they were no longer who they knew they were. Many left: there were 11 or 12 prominent Creole families who went to what later became Tulsa, Oklahoma, and established this very vibrant, successful community there. Many went to the Caribbean, because that was where they had originally come from. They came from Haiti and other parts of the Caribbean in 1803;when the revolution happened there, they had exited because they were privileged, right?

The whole history in and of itself, and placing Macbeth in this time… it was a tremendous script. I had a lot of latitude: Lenny trusted my vision of what could happen with it. I was allowed to create the performance environment, largely through projection. There were very few physical props on stage. I did an animation of a river scene, with the water flowing by and the clouds rolling slowly in the sky. I really enjoyed the challenge and excitement of the live performance, creating an illusion that allows the audience member to transcend and immerse themselves in what's going on in front of them.

Details of stage projections created by Philip Mallory Jones for Lenwood Sloan’s Vo-Du Macbeth (2011).

Another live piece was with Paul Carter Harrison’s Doxology Ring Shout: Praise Dance for the Doxy, also a multi-year involvement that I began working on in 2000. That performance was in 2014 in the Baldwin Burroughs Theatre at Spelman College here in Atlanta. The other collaborators: Dwight Andrews, composer and musician; Diane MacIntyre, choreographer; and Johari Mayfield, a performer-dancer. Dwight composed music for it and assembled two jazz singers and an ensemble of musicians. Diane and Johari worked out the choreography for the piece. There was a lot of animation and, again, a very sparse physical performance environment.

I find it very exciting to work with performers, actors, dancers, and musicians. Some of my most rewarding production experiences have not been as the boss, as the director, as the person with the controlling vision of the piece, but as a tool for that director. It's a very satisfying experience to be on a set and just wait for the director to say “Go,” among people who think the same way, who are prepared, who know what they're doing and are ready to do it. That sense of competence, attention, and focus—knowing why you're there: you're there to serve the director and everybody is ready for that—I find that totally gratifying.

Tyler Maxin: You also had a long collaborative partnership with your mother, Dorothy Mallory Jones.

Philip Mallory Jones: She, myself, and Gunilla made a piece called The Trouble I've Seen (1976). My mother had taken it upon herself to travel, mostly alone but sometimes with a photographer, around back roads in the hills of south and central Georgia, looking for old Black people. She would just get in her car and start driving with a raggedy little quarter-inch cassette audio recorder, a bag of snuff, and a bag of candy. She would approach these people on their porches or in the field or whatnot, and just ask if she could talk to them. They would tell her stories about their childhood memories and what they heard from their elders. These stories went back into the 1800s—she was talking to people who were pushing a hundred years old or older in the mid-’70s.

What they remembered went way back. She did this for a good year, also collecting photos of these people by this photographer. Eventually she started sharing these tapes with me, and I started sharing these audiotapes with Gunilla, these audio tapes. Gunilla and I decided that this project should be captured on video and interpreted. Out of that came The Trouble I've Seen. Many years later, in 2014, I moved to Atlanta briefly. At that time, my mother Dorothy was working on a volume of poetry. She wrote novels and poetry and essays. She was working on this series of poems called Basic Black, and had this idea of a book of her poems with image compositions by me.

She just turned over the stack of poems and I started going through them and making associations with archival photos from our family and from other families, because I had amassed a large collection of family photos from flea markets and junk stores and eBay. I called it "generational amnesia," families just discarding their histories or for all kinds of reasons. Now, these things are no longer important or just get lost. At the time, I was living next door to Dorothy, so our collaboration was really a matter of walking across the driveway from one house to the other to talk about things. Lissen Here! evolved over the course of a year and was first published in 2005. And then I redid the whole thing in 2019, shortly after she passed away. That too, like the work I had done with Gunilla, was altogether based on this mutual respect and understanding about the other's process and aesthetic.

That dynamic was interestingly reflected based on what Teshome Gabriel called "shared language and retained secrets." When I ran across that phrase in an essay on nomadic aesthetics that Teshome Gabriel wrote some time ago. That just really made sense to me. And that in fact was the basis of the conversation between Dorothy and me. Now, we came from the same place; different times, different circumstances, but we knew so much of the same things. In our mature artmaking process we could interpret and express this understanding both to each other and outwardly, but the overall exchange between uss was based on something very solid and old. We were able to really elaborate on each other, on each other's visions through that work.

Images: Two stills from Philip and Gunilla Mallory Jones, The Trouble I've Seen, 1976; Cover of Lissen Here! by Dorothy and Philip Mallory Jones, 2019, Alchemy Media Publishing.

Tyler Maxin: When does the online virtual world Second Life come out, and when do you get interested in it?

Philip Mallory Jones: I was introduced to Second Life in 2006 when I went to the Aesthetic Technologies Lab at The Ohio State University as the only full-time Resident Artist. Katherine Milton, Ph.D., was the founding Director and—as on several significant prior occasions—she pointed the way for my inquiry and creative efforts. I fell into Second Life like Br’er Rabbit in the briar patch. I had seen/heard this platform characterized (and marginalized) as a “game.” Perhaps that is an apt descriptor for some users and dismissive commentators. For me, it became a studio. Within its limitations, in the early years, I found great capabilities for model-making, real-time animation, world-building, and storytelling. Audiences were both in-world avatars and “real”-world persons.

The first piece in this virtual studio was In the Sweet Bye & Bye, an Immersive Memoir. The starting point for this installation was Lissen Here!. Through the development of that work, I was keenly aware of the volumes of backstories behind the simple poetic monologues. My first inclination was to design a physical gallery installation, because that’s all I knew. I did this using the low-end digital 3D apps available to me, with marginal results. I was also invited to mount a physical installation of mixed-media work at the art gallery at Arizona State University in 2005. This exhibition included my early 2D photo collage prints and the book Lissen Here! on a pedestal, video projections, and displays of animations and videos. Standing in the space, I was struck by the inadequacy of this presentation concept. The works spoke to and commented on each other in ways that were not conveyed by this traditional fixed form. I imagined the pieces exploded in the space: engulfing the viewer, dynamic and layered.

On the Second Life platform, some things are possible that are not possible in the physical realm. For my purposes, the ability to configure the installation space to fit the content, rather than the other way around, was a critical and liberating capability. The installation enclosure for In the Sweet Bye & Bye became 12-sided. This corresponded to the number of collage scenes that comprised the metaphoric narrative. It also coincided with the Pythagoreans’ theories of the meaning and metaphysical characteristics of certain shapes.

Another feature of Second Life is that text mapped onto a transparent panel reads correctly from either side! That solved major problems I faced with a physical installation. A key concept of the piece was that of reading the texts and images in three dimensions. Each panel was a self-contained story, but reading through the panels and seeing more than one simultaneously creates something more complex. This concept is derived from the ways in which texts are arranged on the walls of the Temple at Luxor, as explained in Le Temple de L’Homme by R. A. Schwaller de Lubicz.

The installation is also arranged with each panel and wall section at 30, 60, or 90 degrees to any other. As the avatar moves around in space, panels, texts, and images appear and disappear, depending on the avatar’s position and direction of gaze. Thus, the installation is never the same twice and different visitors will see different configurations of text and images. Avatar position also triggers animation and sound events.

A confirming moment occurred during the opening reception for the installation in 2007. The avatar for a journalist based in Paris moved through the panels for a few moments then spoke to me, saying that she was uncertain about her ability to understand the work as she was not fluent in English. I suggested that she simply look at the images and animations, noticing the layers of imagery created by the avatar’s movement and shifting point of view. After a few minutes, she commented that she perceived she was “in the presence of ghosts.” Perfect. Though she might not understand the nuance of the language, or the specific cultural, political, and social history in the texts, she experienced an emotional and visceral connection. She perceived the essence of my intentions—to convey truth, beauty, and power.

Images from In the Sweet Bye & Bye: an immersive memoir, Philip Mallory Jones’ Second Life exhibition, 2007. Left is Jones’ pseudonymous avatar in the virtual environment, Jacque Quijote.

Tyler Maxin: Had you played any video games or similar before experiencing Second Life?

Philip Mallory Jones: I played three games in my life, aside from early Pong. In 1995 I was introduced to modern games, again thanks to Katherine Milton. Myst was a delightful revelation. Before that, it had been twenty years since I had paid any attention to video games. While I enjoyed the play and the mystery narrative, I also approached it as a research endeavor, informing myself about the current ‘state of the art.’ I got excited about the possibilities and opportunities that disc technologies enabled for animation, audience engagement, and world-building. I’m not so interested in the hardcore puzzle-solving, but certainly enjoyed the gameplay. I also appreciated the game’s aesthetic and the detail in its visual design.

I was intrigued by how the makers, Rand and Robin Miller, created moments of authentic experience. Fear, trepidation, anticipation, gratification, relief, and a sense of freedom to explore and discover were all happening in my head. I loved the experience of getting lost in the story and the place. It was intoxicating. I could see immediate application and adoption in my own work.

Katherine got a job at Ohio State University in the early 2000s, and I went there as a resident artist at the Aesthetic Technologies Lab. When I got there, she told me, "World of Warcraft is really interesting. You should look at this." So I did, and again, this was research: I played it day and night for four weeks, until I got to the point where I needed to either play this game for its own sake or stop and do something else.

The third game I played was L.A. Noire. I knew nothing about it other than the name and a promotional graphic, but went out and bought an Xbox 360 to play. I played it for five or six weeks, but this time I went through it with a walkthrough guide, and each step of the way I'd read the guide so I knew what was coming, what I was supposed to be doing, and what to look for. I loved that game.

Tyler Maxin: So you phase out of Second Life in 2010–11, and focus on Unity. Is that around the same time you're also developing the Bronzeville idea? Walk me through a bit about how that came together and what that shift was like.

Philip Mallory Jones: The beginnings of the current work, Time Machine: Bronzeville Between the World Wars, Tales of Speculative Fiction in Virtual Reality, really started in Second Life in 2007. The intention of In The Sweet Bye and Bye was to explode the print-page compositions of Lissen Here! plus other 2D collage, video, and animation work into a three-dimensional virtual online installation. The next idea was to move the viewer from looking at images and text on panels to situating the viewer in the scenes. Bronzeville Sketches, in Second Life, was the next step in this transposition.

Within the modelling and size constraints available, I built a concept sketch of a neighborhood; I combined 2D images mapped on 3D structural forms and 3D modelled objects. An impression, or illusion, of being in the South Side Chicago environment, circa 1940. Successful in some ways, this project also made clear the limitations that the Second Life platform placed on fully realizing my vision for the immersive interactive experience that I was trying to achieve. This required more powerful modelling and animation tools. It required more precise control of all aspects of the build, especially the lighting. For example, real-time shadows were not possible (at least not on my system) so I made silhouette objects in shadow shapes that I positioned on the ground to give the illusion of shadows. This work-around sufficed for the purposes of that developmental project, but altogether the Second Life platform just became too limited for my vision, intention, and ambitions.

I arrived at this crossroads at the same time that the pricing structure for Second Life changed. Educational institutions no longer got substantial discounts on space allocations and I needed more area and bandwidth.

Tyler Maxin: Right. So basically since then, if I understand correctly, you've been focusing on Unity and then this is kind of the various stages, or developed stages of development of Bronzeville: Between the Two Wars, which is now kind of a VR project. Can you talk a bit about it?

Philip Mallory Jones: By 2010, I was working exclusively in offline 3D modelling and animation environments: Carrara 3D, DAZ 3D Studio, and SketchUp. My eye was on developing components for import into the Unity game engine.

The initial concept for Bronzeville Etudes & Riffs (2013-2019) was as an immersive graphic novel. I was building a “storyworld,” as cinema/video scholar Patricia Zimmermann terms it. I had it all in my head and it had been germinating since Lissen Here! The characters, the narrative dramas, the archival research, and first-person accounts were coming together in a dynamic immersive illusion of a time and place. It was very exciting, energizing, and liberating.

This phase of development also brought my mother, Dorothy, and my brother, Donald Brooks Jones, into the project. Both accomplished writers and researchers, they contributed to the narrative development. Many of the scenes and vignettes were based on oral history recordings that we made of Dorothy’s recollections of people, places, and events. She had been there—witnessing, participating. She and my father, Harold Brooks Jones, were part of the founding group of the South Side Community Arts Center. Liz Catlett, Charlie White, Bill McBride, Nat Cole, Margaret Goss (Burroughs), Eldzier Cortor—these were their old friends and running buddies. Some of my earliest memories are of being in artists’ studios, exploring among the towering canvases (I was very short) and fascinating clutter. Dorothy used to jokingly remark that the South Side Community Art Center began in Margaret’s closet and in the big shoulder bag she would tote around. Nat Cole was a familiar guest for Sunday dinner. My father would give him a quarter, so he had carfare to get back home. In elementary school, Nat had the nickname “Shoebooty,” because he would come to school wearing one shoe and one boot.

In 2014, after a visiting faculty position at Colgate University as The Batza Distinguished Scholar in Art and Art History, I moved to Atlanta. The initial impetus was proximity to Doxology Ring Shout. This move also put me in easy proximity to Dorothy and Don. We established a routine of Sunday morning confabs at mom’s house to discuss the narratives of the new project, Dateline: Bronzeville (2017). This was an immersive game concept set on the South Side circa 1940. The protagonist is Runny Walker, ace photographer and investigative columnist for the Chicago Advocate. Through this vehicle, which is familiar and accessible, we could weave the stories and create the world that had been germinating for the past ten years.

As an AAA game, Dateline: Bronzeville eventually got submerged in the mire of access to resources, which are all about money. Don decided that he would take on the challenge of composing our mystery narrative threads as a novel. While developing the game narrative, I had also, of course, been composing the 3D scenes. The 8 Ball Pool Room, Oza’s Deluxe Café, Pearl’s Beauty Parlor, the Top Notch Barber Shop, and many others were already finished 2D print graphics. Dateline: Bronzeville would include color images interspersed in the text.

Images: two selections from Philip Mallory Jones’ Bronzeville image series, Jammin’ After Hours and Champ’s Boxing Gym, circa 2019.

I exhibited a selection of prints of Dateline: Bronzeville scenes at the Rebuild Foundation gallery on the South Side in 2016–2017. I was enjoying the modeling of the scenes and composing the vignettes as stage sets. With a fixed point-of-view and frame, I was able to get very detailed and nuanced in the compositions. I could work at a productive level without struggling with additional daunting learning curves and obstructions due to inadequate hardware and software. For several years, I worked in Carrara 3D, modeling characters and places, and creating the storyworld. This resulted in the fine-art print portfolio album, Bronzeville Etudes & Riffs, in 2019. I also re-visioned Lissen Here! Both these projects were executed in the months following the passing of Dorothy Mallory Jones that year at 99 years of age.

Tyler Maxin: You mentioned miniatures and it reminds me of the work ethic needed to maintain a miniature cityscape or something like that. It requires you being very focused on very granular detail and also bigger picture stuff.

Philip Mallory Jones: I think of the work of the last twenty years—from the earliest 2D collage compositions to immersive virtual realities—as memories, real and imagined. For the memories of family, the stories and histories are held in the treasured family photos, oral history recordings, artifacts and heirlooms. My brother Don is the family genealogist, having traced our lineage back to 1822. That’s a long road, from the plantation in Franklin County, Kentucky. Another research source is the archives of the African American press of the day. I’ve spent hundreds of hours scouring the database of the Chicago Defender, the journal of record for African Americans in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. The Defender was distributed nationally. Pullman porters on the Illinois Central risked jail, or worse, for smuggling copies of the paper to contacts in Southern states. The Defender was a communications link between dispersed families during the Great Migration; it covered Negro sports, entertainment, crime, social and political news, and it reported on international events. Runny Walker, protagonist of Dateline: Bronzeville, the mystery novel, comes out of my archival research.

Image: digital gallery view of Time Machine, Jones’ current project reconstructing 3D models of historic Chicago buildings, circa 2021.

The hunt. Yesterday, I was hunting for floor plans and architectural plans for the original Regal Theater, at 47th St. and South Parkway Blvd, on The Square. The center of the world. I went to the Regal when I was young. There you could see all the headliners on stage: Smokey Robinson & the Miracles, the Temptations, Aretha Franklin, the Supremes, Jackie Wilson. Saturday and Sunday matinees always had teenagers dancing in the aisles.

The building itself was a marvel. Opened in the early 1920s, it was the jewel of showplaces on the South Side. The opulent décor was right out of 1001 Arabian Nights. And like many historic landmarks of Black America, it was demolished in the 1960s. The restoration of the Regal Theater and many other South Side treasures and haunts, simulated as virtual reality, is central to the raison d’être of Time Machine.

The Avalon Theater, now called the New Regal Avalon Theater, has been saved from demolition and is undergoing a massive and wonderful restoration thanks to the efforts of Gerald Gary and his partners. I was in the building a few years ago, and vividly remembered being there as a youngster. It was easy to get to on the bus and offered hours of immersion in other realms of experience. The documentation of this restoration is substantial. I look forward to someday tackling its reimagining in 3D and virtual reality.

The development of Time Machine also entails the creation of accurate 3D digital models of many buildings, which can be transposed as 3D prints. This suggests other kinds of research and exhibition presentation possibilities to come out of the research and production work on Time Machine. My ambition is to create a library of architectural models of now-vanished buildings and locations that were at the time singular and distinctive in the country for their architecture as well as their cultural significance in the community.

This project is funded in part by a Humanities New York CARES Grant with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the federal CARES Act. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this oral history does not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Special thanks to Michael Blair and Charlotte Strange, whose editing work made this project possible.

2021 marks the 50th anniversary of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), one of the world’s leading resources for video and media art. As we celebrate this milestone, EAI will present a rotating series of video features from across our collection and publish a series of oral histories with key figures. To keep up to date on our anniversary activities, please sign up for our e-mail mailing list.