David Wojnarowicz: Motion Rhythms with Doug Bressler, Cynthia Carr, Brent Phillips, and Tommy Turner

Since 2012, EAI has distributed a selection of David Wojnarowicz’s films, including the legendary unfinished film, A Fire in My Belly (1986–87). In fall 2025, EAI added four more titles to the catalogue, which together provide further insight into the artist’s numerous collaborations with other artists and musicians.

To celebrate these new works in distribution, EAI is publishing excerpts from a 2012 panel discussion centered around an under-recognized aspect of Wojnarowicz’s art: his plans and preparations for soundtracks. Rebecca Cleman, EAI's Executive Director (then Director of Distribution), co-organized the panel with Brent Phillips, Media Specialist and then-Processing Archivist of Fales Library. Cleman moderated the discussion with Wojnarowicz’s former bandmate Doug Bressler, who was collaborating on a soundtrack for A Fire in My Belly (1986-1987) with the artist; Cynthia Carr, author of Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz; and Tommy Turner, filmmaker and Wojnarowicz collaborator. A seven-minute edit of Beautiful People (1988), with a soundtrack added by Wojnarowicz’s 3 Teens Kill 4 bandmate Jesse Hultberg in 2011, and a thirteen-minute version of A Fire in My Belly with the recently-discovered sound component accompanied the discussion. This conversation was transcribed by former distribution intern George William Price in 2012 and has since been edited for length and clarity.

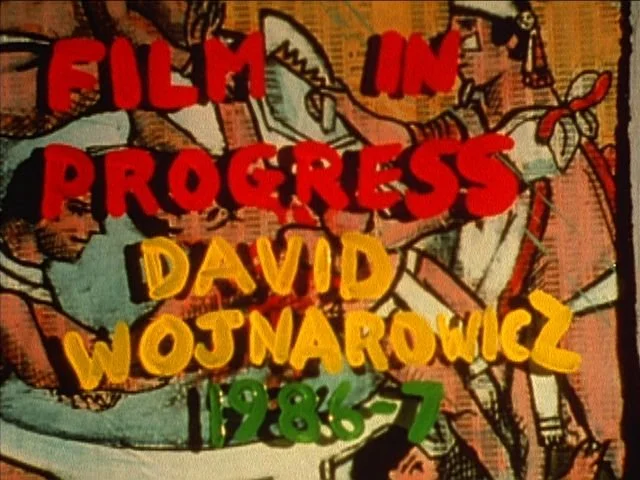

David Wojnarowicz, A Fire in my Belly (1986-1987).

Brent Phillips: When Fales Library first started doing the preservation of David’s films it really was for research purposes. It was to allow scholars and students to be able to get a sense of who David was as a filmmaker. So the fact that David’s films aren’t complete was actually not a problem when we first started preserving the films. It was actually a plus. There was research value in the fact that his films weren’t complete. Then we started getting asked for the films to go to festivals and screenings, and it always came with a great deal of explanation from me, that what we have is not exactly the way the artist intended it to be seen. We began to scour David’s papers, trying to find anything that we could about his work as a filmmaker—the production and the presentation. Thankfully EAI and PPOW Gallery, who represents David, also joined in the mission and started asking his collaborators and peers for their memories. I am very thankful for that because we weren’t finding all that much in David’s papers.

Very quickly, just a little about David’s papers: it’s much more than 128 linear feet. It’s about 200 boxes at this point. The 83 reels of film doesn’t mean there’s actually 83 films, it’s more or less how many rolls of film were in there. It’s a lot of David just grabbing his camera and filming ants or tadpoles or snakes. We have now digitized almost all of the 382 cassettes. They run the gamut from audio journals to his telephone answering machine tapes, which are very revealing, right down to found sounds and everything else.

[...]

In 2003, we received a lot more to [add to] the collection, including [a reel, titled] “Mexico, etc. Peter, etc.” We didn’t really know what it was, so we wrote a grant to NYSCA (New York State Council on the Arts) and they gave us money to preserve it. As we were watching it we realized that the second portion of the film very much looked like A Fire in My Belly.

We started really looking at the film “Mexico etc.,” and we realized that it has shots that were intended at some point, possibly, for A Fire in My Belly, but it was on this other reel of film. He actually even notates “hand receiving money,” “man masturbating” and a couple of other things. He says it has to stay in this order; that’s how planned he was and how the shots were gonna be made. The beginning of the film actually is some footage of Peter Hujar in his hospital bed, and he’s already deceased.

So we found in one of [David’s] journals from 1987 this whole elaborate description of a film that he obviously was thinking about making, and there’s moments in there that are exactly what was at the beginning of that “Mexico etc. Peter etc.” reel. At the bottom, ideas for sound accompaniment: Albinoni's Adagio in G Minor, Pachelbel's Canon in D, and drums.

So we didn’t know what that reel was, and it came to our attention that a lot of the footage was used in Rosa von Praunheim’s 1989 film Silence = Death. So we actually went back to the original film canister, and, sure enough, in pencil, is “Michael Lupetin”—he is one of the producers of that film.

So, we are pretty confident using contextual clues that this is how that footage got there. Of course, that footage in [Silence = Death] has a soundtrack. That is the “Mexico Soundtrack,” and it’s one of those things in David’s papers that we were always like, “What the heck is this?” PPOW organized this great meeting with Doug [Bressler] and Tommy [Turner], and they recalled doing this sound recording. When Doug heard it, it was interesting because he noted that the Maxell brand [tape] is what you would do your final mixes on. So again, it was from those sort of contextual clues that we were able to really glean from the archive, but we wouldn’t have been able to if it hadn’t been for other people around to share their memories.

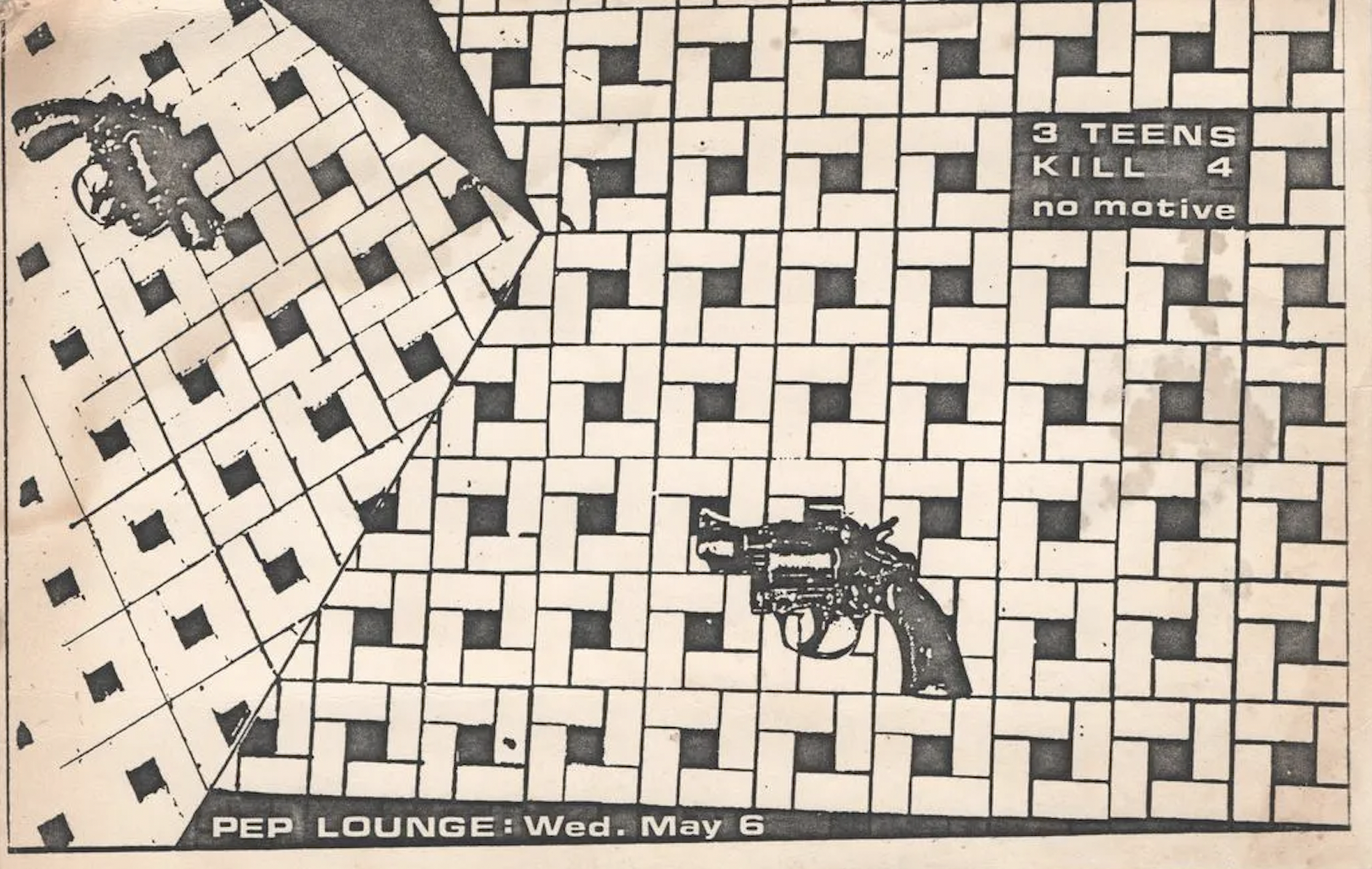

One of the things about the [Fales] “Downtown Collection” is that it all interacts with other things. David is in the “Dennis Cooper Papers” and in the “Sylvère Lotringer Papers.” They all communicate with each other. We recently got the Pat Iris and Emily Armstrong NIGHTCLUBBING archive which is this kickass collection of live musical performances around New York, including live footage of 3 Teens Kill 4 in 1980 at the Peppermint Lounge.¹ We kinda freaked that day; we were like, “Wow, this is pretty exciting.”

3 Teens Kill 4 show flyer by David Wojnarowicz, ca. 1980s. Image courtesy of the Estate of Brian Butterick.

Doug Bressler: I remember looking back at the Peppermint Lounge footage and I started thinking about how great he looks up there [on stage] and how brilliantly talented he was. Not just as writer, as a filmmaker, as a painter, but he could also sing, in tune, beautifully and shake his tailfeathers.

But it’s really interesting when you think about David’s work. You’ve gotta kinda see his work as a whole. I started looking for some of the commonality in his films and music and started coming up with things like collage and layering and clipping things and rearranging and reusing. Always going back to the same concepts over and over again, and, for whatever reason, when he did it, it wasn’t like he was rehashing stuff, it was always new and fascinating and interesting.

He was a real joy to work with. When you worked with him one-on-one, you know it was one of those classic things with geniuses, it was like you were the only person in the world, the only guy in the room. You always felt confident there was going to be a positive outcome when you made art with David because he was so good at it and also because it was the one thing where he knew there would be a positive outcome. So many whacky things happened in his life, but I think he knew how good he was on a certain level, and so he was very happy when he was making art, and he was very happy when he was making art one-on-one. So that’s why you see so many great projects that he does with individual collaborators. All the things that he did one-on-one were always really brilliant.

As far as the “Mexico Soundtrack” goes, I actually can’t claim that I ever even heard the music that I made with David [until now]. So it’s kinda interesting to see what he did with it. It’s also interesting how the whole thing happened because Cynthia found that “Mexico Soundtrack” tape at Fales. I knew that I had worked with him on stuff that contained Mexico material, but I didn’t really think about it at the time, when A Fire in My Belly first came out, that those two things were specifically going to be used. I thought it was going to be a movie about Mexico, specifically, and not A Fire in My Belly, which is about a lot more than Mexico. One of the things David did in the band was use the tape recorder like a guitar solo. There wasn’t really a guitar solo musician in the band at that point. His tapes, especially the ones where it gets really crazy, were the guitar solo. If you’re a brilliant musician but you don’t play any instrument, what do you do? He used all of his resources and all of his talents to be like the guy you were looking at when he was in the band without really ever playing like a real instrument.

DB: I worked on a lot of soundscapes prior to working with David by myself. Working on these kinds of things with him was different because he came with so much real live source material. A lot of times I was just trying to build it up from musical instruments—electric guitars, rhythm machines and all that kind of stuff—but he came with a lot of found source material. He was also an amazing improviser. I think one of the ways that he wrote poetry was to speak into a tape recorder and just record, I guess, whatever came out. When we were fishing through stuff to make our 2011 performance more authentic, and bring David’s voice into the performance without it being too tacky or anything, I stumbled on some spoken word stuff he did.²

Voice recording by Wojnarowicz ca. 1970s-80s. Courtesy of Doug Bressler and The David Wojnarowicz Foundation.

What I’m getting at is that you hear the way he repeats things, he’s clipping himself in a way, he’s doing the same thing he did with that “run away, change my name, become a woman.” He’s doing that thing with himself and to himself.

DB: You can hear there what he did with tape manipulation, or what Jesse [Hultberg] did. They may have been working on it together at that point, but you can kind of see where everybody was at. You have to remember that all this was done on analog equipment, so it certainly wasn’t as easy as it is to do today. You were actually either re-recording stuff and dealing with generational loss or you were doing like what Josh Fried³ used to do, which would be to actually use a big 4-track [recorder] and just dupe, edit, and tape things together. I’m pretty sure for the most part when David worked, he was just working with two cassette decks, just bouncing things back and forth, which yields a lot of artifacts and stuff like that, but it sounds really good.

Rebecca Cleman: You worked on a lot of the installations or sound projects with [David] as well. Could you talk about that process?

DB: David liked spectacle, he liked observing spectacle, and he also liked creating his own and then mashing those two things together. I think those were the kind of things he was trying to achieve with installation pieces. There was always that whole dark thing with David, and a lot of his stuff was kinda grim, but when you knew him or his process, he was very joyous, so it was an odd combination of subject matter. There is this thing about creating spectacle that was part of the filming and his art in general and layering the two things—real spectacle and his own creation.

RC: You had a really nice way of talking about his, I think you said “plastic use of sound,” which really makes sense to me, especially with what you are saying about his analog process and the assemblage of sounds and collaging them together in this very plastic way.

DB: I think he was somewhat fearless when he made art, he would just use the tools as he saw fit. I think he would see people doing something for five seconds and then he would want to do it himself and, you know, grab the camera away, grab the drums away, and it pretty much was off to the races.

RC: That’s great. Thank you. Now Tommy.

Tommy Turner: I used to do a magazine called REDRUM that David made these Archie comics for. He would cut them up. When Archie is getting a blowjob by Veronica he would cut out a piece of the flesh from the arm and put it down and make a dick out of it. (Audience laughs.) They were pretty funny.

I met David around 1981? I’m not sure. Cynthia would know better. (Audience laughs.) We worked together at the Peppermint Lounge, which was this bar-club. There were lots of bands there and that’s where that 3 Teens Kill 4 video recording came from. We would hang out, and we would go out after work. We became friends and we would go and eat eggs, he loved to eat eggs. Then we would go out and break into abandoned buildings and take pictures, just kick the doors open. We did that for quite a while, or we would go to the piers on the West Side. David would always have some stencils and some spray paint and would tag wherever we were. He would tag his burning house image or whatever. It was really fun to hang out and break into abandoned buildings with him.

Then we went on a bunch of road trips, and during one we were with this guy, Richard, and he dosed me and David with LSD. Then me and David went out and had a really good time. We bought all these fireworks. We were in Virginia. We were in David’s old station wagon, and he had this rubber frog on his dashboard. You had to put bugs into it to keep it going, like it was this old thing, but it was filled with bugs, and that car never died! (Audience laughs.) It worked somehow. We were in Virginia Beach and we’d bought all these big rockets, and we broke all the sticks off of them. We were out on the beach tripping and igniting them. If they don’t have a stick they don’t go in one trajectory, they kinda go everywhere. So it was like being in Vietnam or something. (Audience laughs.) Stuff blowing up all around us. When we got back to the hotel we were staying at, Richard, who had dosed us, had a bad trip. We had a great time.

Then we went to Mexico where David filmed the footage for A Fire in My Belly. He was twisted on this idea, he was like, “OK, Tommy we gotta find a bear riding a tricycle,” and I’m like “What the fuck?” So we were perusing all these magazines and looking up these circuses. We never found a bear riding a tricycle, unfortunately. But we made a lot of the footage from A Fire in My Belly from one of those circuses where there were four guys and two girls, and they were everything. They were the clowns, they were musicians, they were the acrobats, they were the guys spinning around in the wheel on a motorcycle. It was just them. So that was pretty good, and David got some good footage from that.

David, while we were travelling around, would always have a tape recorder and he was taping everything, like street sounds, circus sounds, and just compiling all this stuff. We were shooting film constantly, and we went to a Mexican wrestling match, which is in that film also. David had the wherewithal to hire a taxi driver to escort us, which was a good thing because we were in there filming this Lucha Libre Mexican wrestling, and these security guards came out, grabbed us, took our cameras away, and were hijacking it. If that had happened, A Fire in My Belly would have been a different movie because David would have lost some footage, and he would have not been able to film anymore. Our cab driver argued with this guy. We asked,“What are you talking about? Are we going to be able to get our cameras back?” He said “No, no, no, no…they just want a bribe,” and I’m like “Well how much?” It was like two dollars, and I was like “Just give it to him!” He said, “No, that’s not the way we do things here, you have to fucking barter with them.” (Audience laughs.) I was just thinking that both of our cameras are going to disappear. We got them back and David got that footage for A Fire in My Belly from that. It could have been a moment where that stuff wouldn’t have existed.

RC: I also wanted to ask you about Where Evil Dwells (1985) because you had a good story that ties into the process of working with David, or mirrors some of what Jesse was saying about Beautiful People (1988) and not getting the sound together in time. You had talked about delivering Where Evil Dwells, or you had a screening at the end of one festival?

David Wojnarowicz with Jesse Hultberg, Beautiful People (1988).

TT: Yeah. Tessa [Hughes-Freeland] was doing a thing called “The New York Film Festival Downtown,” we were working on Where Evil Dwells, and it was last minute.⁴ We were two hours late, and we were editing the sound on a 4-track recorder, just talking over the picture. We only had a couple of minutes. We just ran down there with the footage and showed it at the last second. That was also a fun thing to work with David on because we got chased out of so many places. We would go to these suburban malls and film stuff, and they would just hate us because we would just wreak havoc everywhere and film it. People doing all this fucked up stuff and somebody with a Super 8 camera filming. We’d get chased out of so many places.

RC: You had some really great ideas about lo-fi special effects in the movies, like in the beginning of Where Evil Dwells. Where Evil Dwells was 1985, so it was before your trip to Mexico that you finished that?

TT: Yeah.

RC: All that exists now is a half hour trailer?

TT: Extended trailer.

RC: What about the sound? It’s all sampled music on the soundtrack for the trailer, but what was the sound like that you just described working on with David at the last minute?

TT: We just had a 4-track tape recorder, and we were both frantically saying stuff and putting in music. This guy Jim Thirlwell gave music to us for that.⁵ We were just laying down all these tracks at the last second and we had our tape recorders that David had recorded shit on. We were putting that over the televangelist Jimmy Swaggart, who we had recorded off an AM radio station at the time. So we were just overlaying these sounds that we had, like jackhammers or whatever.

There’s one other thing that’s kinda funny about when we were making that film: David introduced me to this place called Caven Point in New Jersey. It was this desolate location past some old Navy base that doesn’t even exist anymore. We went there, and there was this car that had fallen off of a bridge. I don’t know how it got there. It was sticking out of the ice. So David had this Station Wagon, and we were collecting Christmas trees and just jamming them into the back of his car. We wrote “Where evil dwells” in the ice outside the car. This was January; they were all old Christmas trees, and we were gonna ignite the car but it got too dark, and we couldn’t film that night. So we went back the next day, and there were firemen all over and this place was in flames. We were going to film Where Evil Dwells on the ice, and film when the ice melted because of all the Christmas trees, and then we’d put it backwards so it would just appear there. But we get there and there are all these fireman, and we’re thinking, “Oh fuck some kids must have gotten our idea!” They ignited the shit. (Audience laughs). We found a lot of weird stuff there. That doll hanging from the bridge. I don’t know why that was there.

DB: I think he took me to see a dog carcass there once. He was like, “Hey you wanna go and see a carcass of a dog?” And I was like, “Sure,” and you’d get in the car and he’d drive you with this encrusted dashboard.

TT: Right! With larvae and stuff?

RC: I want to be sure that we get Cynthia’s voice in the mix here. Sorry, I didn’t mean to cut from the dog carcass to (Audience laughs.)…you don’t have to comment on that, Cynthia! I just wanted to make sure that we had time for you to weigh in on this conversation.

Cynthia Carr: Well I was just thinking that after that whole “ants on a crucifix” thing [in A Fire in My Belly] started, I talked to Tommy because he’d been there when David filmed the ants, and this was now on the front page of The New York Times. I remember asking Tommy, “OK, what did David say? Why was he filming the ants? What did it mean?” Tommy said, “Oh he was just grabbing images.” I think this is what David basically did with photography and with grabbing sounds too. He was attracted to certain images and certain sounds and he stockpiled them. He would figure out later what he was going to do with it exactly. I also think that he used the film camera to connect emotionally to something.

I did write this book,⁶ so I thought I’d read something. It takes place after these events in Mexico and comes after the death of Peter Hujar, and some of this footage is on the reel you were mentioning, [Mexico etc. Peter etc]. He began, after Peter died—Peter Hujar who was his great friend and mentor—a new journal in which he wrote that he was going to “film the process of grief.”

He drove out of the city one day to film whatever his intuition led him to, and that was the Great Jersey Swamp. “Virgin forest, primordial place where dinosaurs once slept. All these heavy storm grey clouds these days. Huge dark flapping wet curtains over the stage of this earth.” In that passage he’s actually evoked his painting, Wind (for Peter Hujar), with the images of dinosaur clouds and flapping curtains, but then for him everything he encountered resonated with emotion with his feelings for Hujar, which he probably never expressed while Hujar was alive and struggled to articulate now through the camera. He ran, “shooting automatic bursts of film.” Then went whirling through the trees, filming as he spun until he was nauseated. “Felt my body in some strange way, it’s mortality, it’s thumping heart, it’s fear and loss, it’s small madness.”

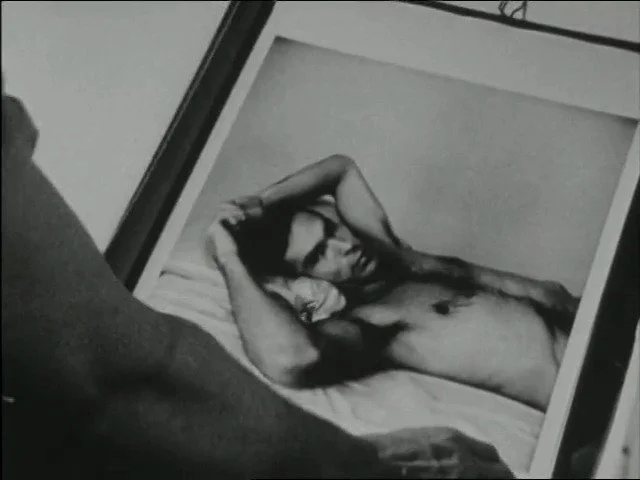

David Wojnarowicz, Unfinished film (sequence in memory of Peter Hujar) (1987).

Later he said that he wished he could have filmed the snowstorm that suddenly engulfed the car on the interstate and the pack of dogs on the road all standing around one dog who’d been hit by a car, who lay there not moving. In the driving snow one by one they sniffed at its form, unwilling to leave it behind. Back at the loft, David filmed all the pictures of Hujar he could find, beginning with one little school photo of the unloved kid Hujar had been. He filmed Jesse Hultberg’s dream of shirtless men passing the prone body of a man from hand to hand. Jesse, eyes closed, took the role of the man gently being passed along. He may have filmed this even before Hujar’s death. Jesse remembered only that it was an image David wanted.

David worked on the Hujar film on and off for about a year and never finished it, but it goes to the heart of what he was doing with his films. He used the camera to capture something that connected him to the world, that allowed him to react emotionally and though he had to wait to get the film developed it seemed instant. It was as immediate as speaking into a tape recorder or pounding out pages on the typewriter, but those two options did not give him a visual image, and he wanted to record each telling detail, like Hujar’s bathtub filling with dead leaves that blew in from a vent in the ceiling.

I also wanted to say that because David was a collagist, really, as we’ve said here, I think he hadn’t quite figured out how to really do that with film because that’s a linear medium. He wrote this letter to Barry Blinderman, the curator of his 1990 retrospective [at Illinois State University], about A Fire in My Belly specifically. What the ants meant, for example, and not about sacrilege, but he also said that he wanted to try to address this problem of film image, to do it like a collage. One part of the letter said, “What I explore in the film is the workings within the surface image so, I split open continuous images and place studio shots or other related images within the splice. The film uses spliced-in images almost as subliminal messages, but each image is used at least long enough to register on the brain, sometimes longer.” So he intended to create the cinematic equivalent of layering or collage but I don’t know that it works.

One thing that happened later in the summer of 1989: he had this experience where he went upstate with his friend, Marion Scemama,⁷ and he happened to get hold of a camera someone had there. It was a fancier camera than David ever used before, and he was able to freeze frames, split screens, do strobe effects, frames within frames. I think that’s something that he might really have continued with because it sort of goes with the way he liked to work anyway. Also, what happens in that footage is he starts doing the thing that Doug and Brent have spoken about, sort of just speaking spontaneously. Also, they were on vacation up there, but David never really took vacations. He was always working.

One day he was up there with Marion and Andreas Sterzing, who owned this camera, and some other people, and they’re all playing badminton. Meanwhile, David has spontaneously composed poetic lines, a voiceover, while he’s filming some of this stuff around the lake. Like this line: “Sometimes my mind is an automobile but my heart is a prison. Sometimes the stars and sky [make] my head hurt.” He came up with a more successful prose poem one day when a green bug landed on his finger while they were driving, and Marion filmed him in the back seat as he said, “I wonder what this little bug does in the world? What is his job? Does the world know it if he dies? Does something get misplaced? Do people speak language differently if this bug dies? Does the world get a little lighter in rotation?” That’s him speaking spontaneously, saying all this stuff. Then in his last show, that turned into a photographic piece of a tiny frog in his hand with the title ‘What is this little guy’s job in the world?’ So he was always creating in that way, relating spontaneously to the world.

Brent Phillips is the Sound and Moving Image Archivist at the Rockefeller Archive Center. From 2003–2016, he worked as an audiovisual archivist at the Fales Library and Special Collections at New York University. His book, Charles Walters: The Director Who Made Hollywood Dance, was published in 2014. He is a graduate of the L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation.

Doug Bressler joined 3 Teens Kill 4 in 1981. After David Wojnarowicz left the band, he and David continued to collaborate on sound works for installations, theatrical pieces and film. He now works as a multimedia artist, in exhibition design and information technology.

Tommy Turner is an artist and filmmaker who is associated with NYC’s downtown No Wave scene and the Cinema of Transgression. While working days as a genetic research scientist and nights as a bartender at the Peppermint Lounge, he rose to prominence through his zine REDRUM and collaborations with filmmaker Richard Kern. Turner collaborated with David Wojanrowicz on the film Where Evil Dwells (1985).

Cynthia Carr was a writer for the Village Voice from 1984 until 2003, specializing in experimental and cutting edge art. She has published the books Our Town (2007), Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz (2012), which won the 2013 Lamba Literary Award for Gay Memoir or Biography, and Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar (2024), which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for biography.

Notes

The Peppermint Lounge was a nightclub that operated from 1958–1965 in midtown Manhattan. Revived in 1980, the club relocated downtown in 1982 and primarily hosted alternative rock and hip hop groups until it closed in 1985.

Wojarnowicz’s former band 3 Teens Kill 4, which included Jesse Hultberg and Doug Bressler, reunited for a three night performance in 2011. For this event, Hultberg created a seven minute edit of Wojanrowicz’s film, Beautiful People (1988), in which Hultberg stars. While the original cut is silent, Hultberg also added a soundtrack featuring the 3 Teens Kill 4 song “Special Reserve” along with found audio recordings by Wojnarowicz, in which a voice states, “What I really want to do is to run away, change my name, become a woman, and forget the whole thing.”

Joshua Fried is a composer and sound technician who performed tape loops and electronic music at legendary New York nightclubs CBGB, Mudd Club, Club 57, Pyramid, PS 122, Danceteria, and Limelight.

The New York Film Festival Downtown, focusing on experimental film and video, was founded by filmmakers Tessa Hughes-Freeland and Ela Troyano and ran annually between 1984–1988.

JG Thirlwell, an Australian-born and New York-based musician and producer, who primarily released music under the moniker Foetus.

Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz (Bloomsbury, 2013).

Marion Scemama is a French photographer and filmmaker. She met Wojnarowicz in 1984, and they went on to collaborate on several works. She also assisted him with his art throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, including his well-known photograph, Untitled (Face in Dirt) (1990).