Hello, Darkness, A Story of Collage and War: Kenneth White on Carolee Schneemann

This December and January, EAI and the Carolee Schneemann Foundation celebrate the prolific legacy of Carolee Schneemann with a series of free programs of film and video available for online screening December 15, 2023 – January 30, 2024. The programs address three overarching themes in Schneemann’s moving-image work: antiwar film and video, sex and images of the body, and winter celebrations.

Kenneth White’s essay addresses Schneemann’s 1967 performance, Snows, and the accompanying film, Viet-Flakes (1962-67) to examine Schneemann’s intricate engagement with the visual dynamics of war from the seat of American imperialism. The themes of war, body, and winter converge in White’s analysis, unearthing in Schneemann’s work a heartfelt dedication to upending the violence of American culture by re-envisioning the role of image-making in constructing a collective political reality. White asserts: “Viet-Flakes evokes snowflakes—so many terrible images were aswirl in American culture by the winter of 1966, and yet the war continued, ‘constant as weather.’ And it evokes truism of flaky American liberal indifference—as if to see is to know. … Viet-Flakes for Frosted Flakes, then: atrocities as common as breakfast cereal. In Snows, ‘bringing the war home’ was a bitter misnomer, for the war was made at home, seething under the snow.”

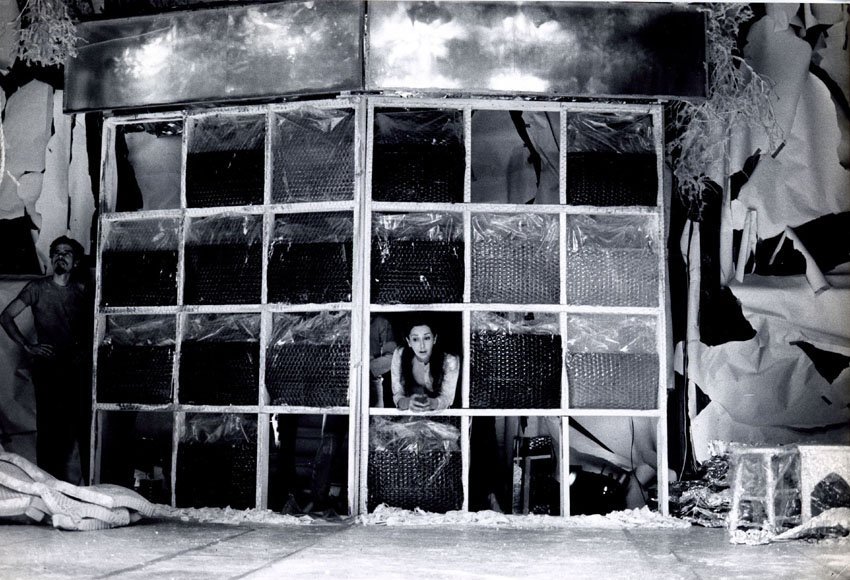

Image: Snows, 1967. Photograph by Herbert Migdoll. © Carolee Schneemann Foundation.

At the end of 1966, Carolee Schneemann made a copy of the front page of the December 24 issue of the National Guardian, the progressive newsweekly based in New York. In the page’s top half, a black and white photograph fills the space. The photograph challenges the reader’s quick apprehension of its subject. We can make out an outdoor landscape, a thinly forested area, under diffuse illumination. A sloping mound at the photograph’s bottom edge, near-distance in our view, and a larger mound at middle distance, occupy the center of the composition. Contrast defines the mounds against darker tones that pock the scene: children—eleven, perhaps more—crouch and dart between the mounds. The bright mounds appear as heaping snow; the children would seem to race among snowpack. But once we note the children’s thin garb, the stalks of tropical plants, the texture of the mounds as more coarse pallor than gleaming crystals, we understand that this is no Christmas Eve winter wonderland but rather a network of trenches. The children run for their lives. The camera is aimed low—the photographer cowers, too. There is no horizon.

Image: Front page of the National Guardian, vol. 19, no. 12, December 24, 1966, and Schneemann's negative reversal of the image.

The photograph’s caption as given by the National Guardian reads: “God rest ye merry, little children, let nothing ye dismay … This is how the young of North Vietnam go to school at Christmas time in the year of our lord, 1966.” The caption presents the children and their ordeal without specificity: they are exemplary of the terror suffered by North Vietnamese children in general under American aerial bombardment. The arch reference to the Christmas carol God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen is further underscored by the over-elaborated reference to the date as “the year of our lord, 1966.” The paper’s denunciation of unchristian behaviour in a style of bitter understatement follows a formal analogy in the photograph between idealized serenity in American Northeast wintertime and the savage violence wrought by that nation upon North Vietnam and its young through devastating aerial attacks, eleven thousand tons of ordnance dropped in December 1966 alone.¹ The caption exploits the confusion by resemblance: a landscape defined by the contrast of light and dark, the games of hide and seek. In the obscurity of the photograph, made by the journalist Wilfred Burchett, the editors of the National Guardian found a weapon of irony against American imperialism.²

If atrocities were not exceptions but rather the rule of the war, as the historian Nick Turse has established, then this photograph and its context, and Schneemann’s appropriation of it, asks us to confront the terms of our imaginative engagement—the aesthetics—of ritualized violence in American national character, in the era of the Vietnam War and beyond.³ In contrast to the wrenching clarity of Ronald L. Haeberle’s photographs of the atrocities near Mỹ Lai on March 16, 1968, or Nick Ut’s photograph, The Terror of War, of Phan Thị Kim Phúc and other children wounded by napalm on June 8, 1972, the National Guardian photograph does not register an extraordinary event. Indeed, its prosaic character is the opportunity for a sardonic caption contingent upon mistaking children in mortal danger for those at play so to elicit a reader’s empathy: ’tis the season.

While Haeberle’s and Ut’s photographs would come to exemplify the war’s pervasive brutality, turning images into icons, Burchett’s photograph seems not to have persisted in the historical record beyond Schneemann’s torn (not cut) excerpt from a copy of the newspaper edition. It is a curious enigma for a front-page feature. There is no record of specific destruction: no raised weapons, no plumes of choking smoke, no gutted bodies. Darkness, but no death. We see little ones rendered indistinct, softened by speed, as they leap from under a thatched canopy, their school, into furrows that envelop them, dark smears falling into rips in the white earth. The children, frozen in the still photograph, frozen in the destiny of arbitrary violence show that violence begins in abstraction, in the games of hide and seek. It is easier to murder children when they are a problem of pattern recognition and collateral damage, of data entry and statistical analysis, of tallies on a calendar. This is how the young of North Vietnam go to school at Christmas time in the year of our lord, 1966. And this is how Schneemann examines the photograph’s effects beyond its left-wing agitprop appeal, to see its qualities of contrast, its extreme tonal range, its illusions of recession and projection from one zone to the next through accumulated textures, coarse to soft, the blur of movement in the children’s hair.

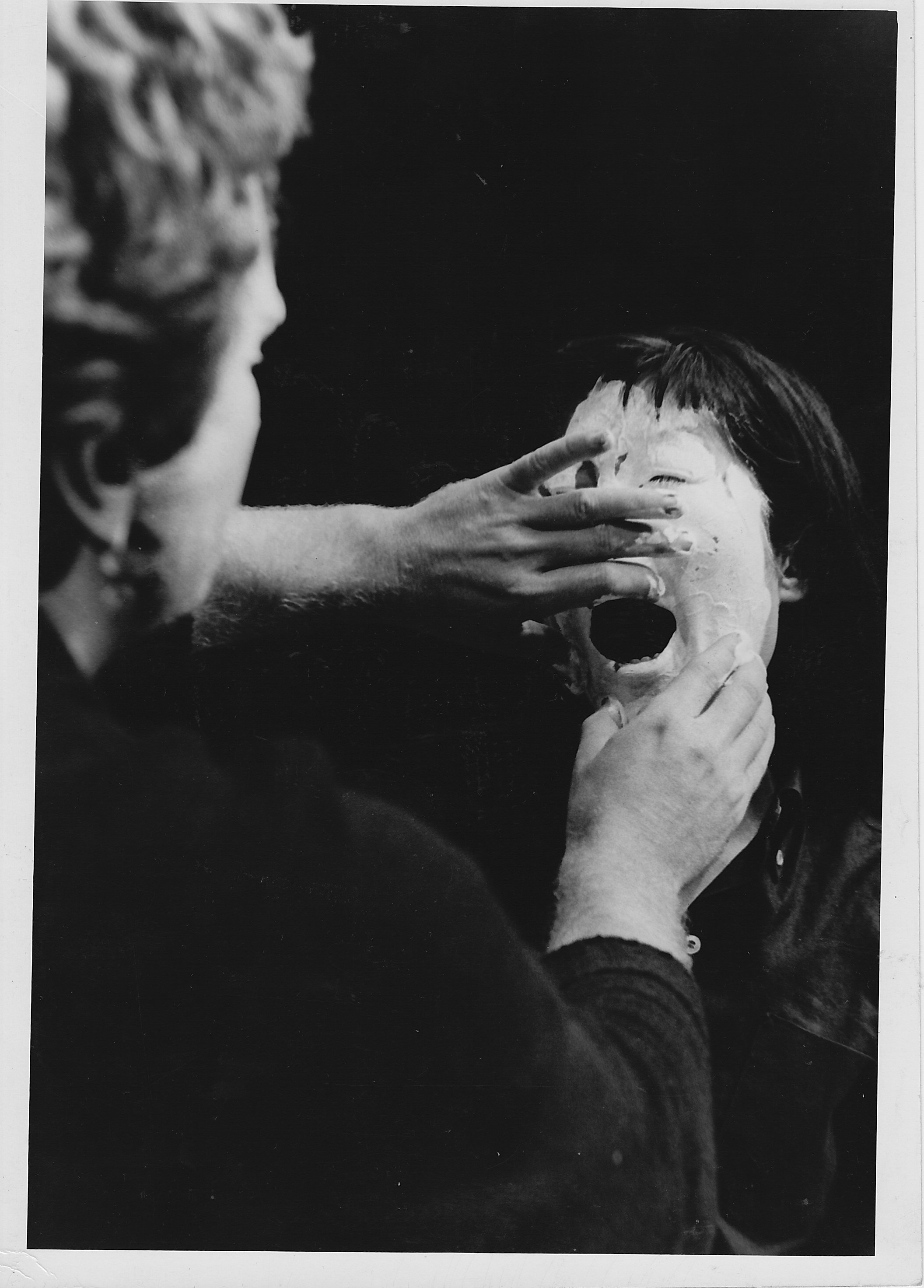

The photocopy is located in Schneemann’s preparatory materials for Snows (1967), her “electronic media system projection environment,” performed at the Martinique Theater, New York, in 1967.⁴ And there is another photographic object alongside the photocopy of the National Guardian front page: it is the same image, in negative. Now the children appear illuminated from within, as like embers, smouldering, half buried in the charred ground. This particular play of positive and negative emerges as a central component of Snows, when the work’s performers execute score note number four, the “Creation of Faces,” in which they apply clown-white make-up on each other’s faces, and later, in the second half, score note five, in which they wrap themselves in household aluminium foil to become “Silver Walkers,” flashing in a cross-fire of strobe lamps amid a darkened theater.⁵ Schneemann works through the effect of the photograph’s contrast by technical inversion of light and dark. She ripped the image from the newspaper, brought it to a printing center, ordered a photocopy of the newspaper page on common office paper, and then further ordered a print of the page cropped to the image alone, without any text, inverted, on semi-gloss photographic paper. “The evidence of the personal experiences of the Vietnamese was reaching us at a great remove, through reproduced photographs,” she wrote, noting, “the unknown outcome of the situations depicted and the ambivalent role of the photographer (whose life was also threatened) ‘taking pictures,’ as people burnt, bled, fled, were tortured.”⁶ In Schneemann’s “taking” of this picture, we discover a decisive clue about the making of Snows, the stakes of its formal experimentation. We can imagine her delight at the snow scene, her puzzlement at its selection by the National Guardian, and then her thrill in apprehending the fantasy of season’s greetings, the contrast between a cheer and a wail, between New York and North Vietnam.

The simple duplicity of the picture evokes a deeper, wintry chill: the severity of a white-out, visibility near zero, how wind does not blow but rather cuts through you, how we gasp at crystals that slice our lungs—not so much exhalation as breath sucked from us—how one must be vigilant for any touch of blue on fingertips and toes, how in travel after dark every snowflake is a firework flash bursting in front of your eyes in the beams of car headlights. Indeed, Schneemann incorporated such imagery as a “winter diary” film projected over her audience in Snows: “the neighborhood of my loft, the Martinique Theater, Gimbels, Greeley Square Park in a blizzard, driving through the whitened city out the West River Drive, into the night and the country landscape.”⁷ Schneemann would seek to induce the treachery of Yuletide, of “tidings of comfort and joy,” on the stage of the Martinique. See how she describes the audience’s entry into the theater by the stage, how they are made to cower, as if amid snowpacks became trenches: “The audience has been led into the theater through the backstage door. In the dark they squeeze through two floor-to-ceiling foam rubber ‘mouths’ and crawl over and under two long planks, which stretch from the stage to the rear wall (across aisles and over seats).”⁸

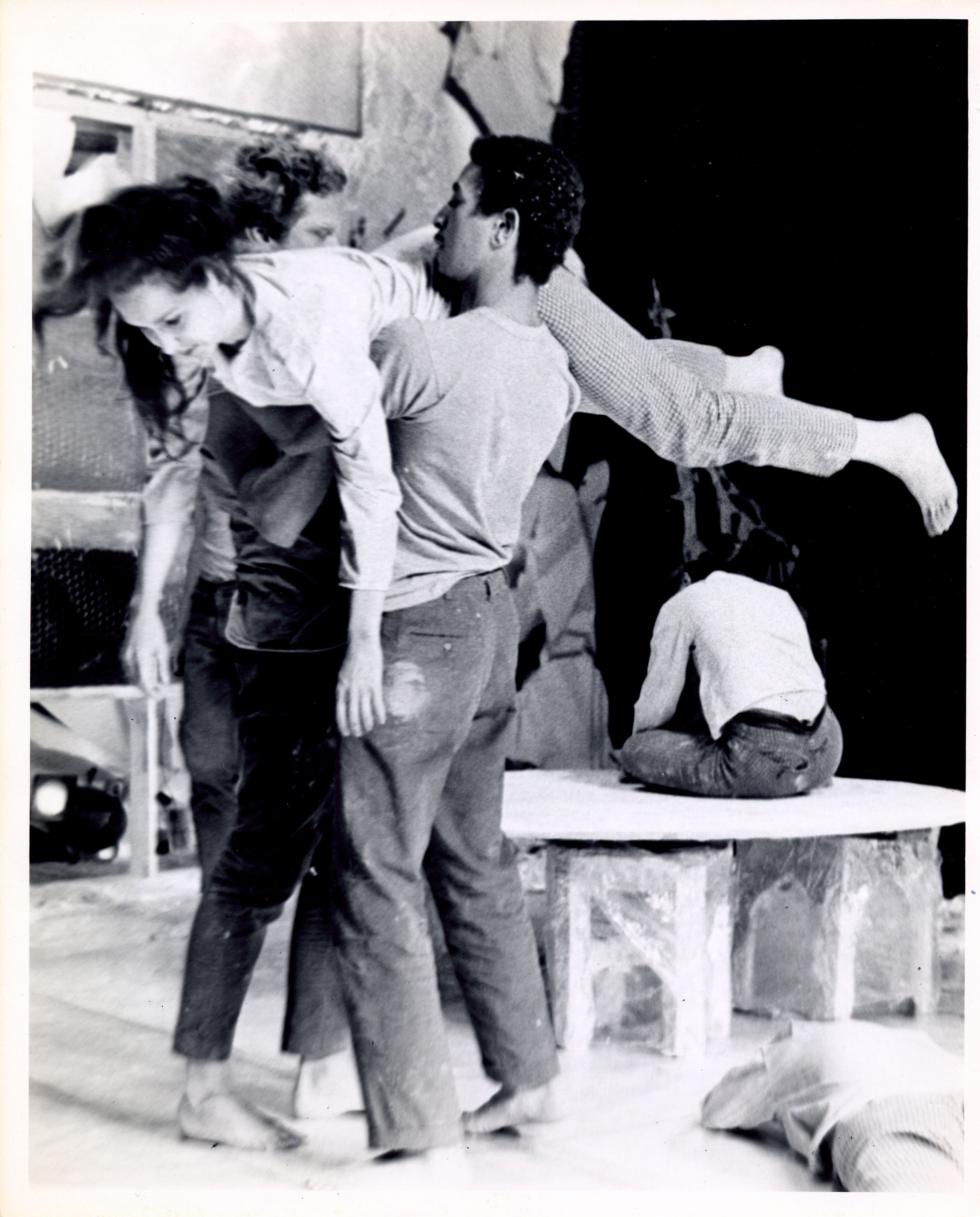

Slideshow images: Snows, 1967. Photographs by Charlotte Victoria. © Carolee Schneemann Foundation.

The photograph and its negative reversal, then, offer insight into how Schneemann sees an image of war: how bodies are constituted by formal properties of light and shadow, reflective and absorptive, dense and translucent, how a body’s weight and heft flatten in the planar uniformity of a photographic image, how she understands the material continuity across the object’s surface as its own kind of evisceration, every snapshot a cut in a relentless negotiation of separations with and through optical processing. It is not a question of foreground and background, but rather of medium and media, ink and paper machine-pressed thin into images of children then stacked at a Greenwich Village subway station. Through Schneemann’s eye, we see the disintegration immanent to the body as a media object, the body as collage.

By 1966, Schneemann’s techniques of reversal of light and dark, positive and negative, were longstanding, fundamental elements of her exploration of vision as “not a fact, but an aggregate of sensations.”⁹ From her early landscape canvases to her “painting-constructions,” Schneemann extended her mode of painting as an aggregate of sensations with and through photographic media. For instance, we might consider an earlier work such as Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera (1963), where the effect of the dense assemblage of materials in the artist’s studio, a former furrier’s loft, is further intensified through the compression affected by the camera’s fixed-focus lens: vision becomes an absorbing, wrenching process for body as much as for eye.

Image: Poster for Snows, 1967. Printed paper. © Carolee Schneemann Foundation.

Schneemann presented Snows in January 1967, in a bitterly cold New York. On the stage of the Martinique Theater, she and her collaborators— “Troopers,” she called them, in a martial pun on theater “troupe”—seven performers including Schneemann herself, and thirteen crew—built a complex series of walls from two-by-four timber, chicken wire and plaster. The frames supported transparent plastic sacs filled with water dyed blue, red, yellow and green, in a gelatinous grid at once translucent and refracting the light, bulbous and imperious in its fixity as a wall and a “water lens.” Around the frames, they attached Christmas decorations, frosted trees and bleached bare branches clotted with white cotton snow, silver paint and glitter, found discarded in dumpsters behind New York’s Gimbels Department Store, the trash of holidays just past. Foam and paper-scrap wreathed the stage’s edge. At center was a luminous white “moon disk,” a circular screen, like the eye of a hurricane, in “a vortex of increasingly disturbing energy.”¹⁰

Schneemann and her Troopers disappeared behind the water lens wall to become flickers of light and color, and then re-emerged through what she described as an “aperture” via a “slow animal-intense crawl.”¹¹ They caked each other in chalky white paint: flashing targets, grotesque baubles on this wreath of slag. A battery of film projectors swung across the space. A range of lamps concentrated and dispersed the focus of the nightly capacity audiences amidst the refractions on the stage. From full beam to sharp flicker, from soft spots to illumination aimed from below, lights revolving and following, Snows affected optical distress as a collaged landscape. Light was a substance for searching, for pulling, in coordination with the Troopers’ actions, who might be “pursuer,” then “interference,” “aggressor,” then “victim” or “object.” “Victim or object endures pulling as long and possible then breaks free,” Schneemann’s choreography directed.¹² The Gimbels winter wonderland was now a dread séance, a conjuring of ghosts.

Engineers from Bell Labs, coordinated through Billy Klüver’s Experiments in Art and Technology, helped Schneemann build silicon-controlled rectifier (SCR) systems to syncronize signals from contact microphones wired to the seats of the Martinique. These registered the movements of the audience and turned their shifts in pressure and posture into commands for stroboscopic lamp arrays, film projectors, and audio playback systems. The SCR system coordinated the speed and intensity of the light pulses and sonic events, which were in turn received by the Troopers as cues for the next episode of Schneemann’s choreography of grabs and falls, lunges and tumbles, relays of predator and prey. Whether or not the contact microphones and SCR switching system functioned as intended is an open question, and beside the point.¹³ For Schneemann, her audience was an accumulation of so many body parts, so many knuckles and tendons, knees and hips, ligaments and joints, stitched and separated by nerves, particular and vital bodies, coming together and coming apart.

Through less a change of costume than a donning of armor for desperate paranoiacs, the Troopers wrapped aluminium foil, donated by Consolidated Aluminum and Reynolds Aluminum, around each other’s arms, waists, legs, and heads, to become the Silver Walkers. With their frail sheaths for body and mind, the Silver Walkers were lurching trees covered in tinsel. They set themselves as figure and as ground, a shimmering surface between image and its disintegration, between animation and stasis: reflective not in the sense of thoughtful introspection, but rather as a property of matter. Now all obstinate surface, the Silver Walkers broke and tore the light as screens not pristine, but pinched and mottled. “Nearly blind in their wrappings,” these scarred, shimmering figures-and-ground walked amidst the audience, guided by blue flashlights like bodies on fire.¹⁴ The foil peeled and fell away from the Silver Walkers in loose drifts, forming ragged snowbanks around the audience, as if the silver halide of the images melted and dripped in the hot lamps of the projectors.

The stumbling movements of the Silver Walkers were all the more precarious for the images of war atrocities breaking around their kitchen-metal shells. In the refracted light, the Silver Walkers animated American soldiers, Lyndon B. Johnson, the mutilated corpses of Vietnamese villagers. The projection series included Schneemann’s film Viet-Flakes (1962–67), a collection of roving handheld close-ups of still photographs by journalists in Southeast Asia and published in anti-war newspapers, such as the National Guardian.¹⁵ Schneemann made the film with an 8mm camera as a bleak home-movie. Viet-Flakes evokes snowflakes—so many terrible images were aswirl in American culture by the winter of 1966, and yet the war continued, “constant as weather.”¹⁶ And it evokes truism of flaky American liberal indifference—as if to see is to know. “Each film spilled out of its fixed frame, projected onto surfaces throughout the theater: spread, pulsing, centralized to have as much physical stretch and shift as the performers themselves,” Schneemann wrote. “It was as if film could be projected back into/onto film, a collision and absorption of images like the collisions of our bodies.”¹⁷ The SCR system registered the audience squirming in their seats. Their passive regard translated into electric pulses, which then directed the lamps and projectors to light them up, connecting their bodily pressure to images from “a Mỹ Lai a month.”18 Viet-Flakes for Frosted Flakes, then: atrocities as common as breakfast cereal. In Snows, “bringing the war home” was a bitter misnomer, for the war was made at home, seething under the snow.

The Vietnam War offered Schneemann a particular opportunity to explore integrity and its loss, in a body, in an image. If Snows shares the anger of contemporaneous anti-war protest theater—and it was produced by renowned Broadway veteran Paul Libin as a work of theater in his Angry Arts Week program against the war—then its dedication to formal experimentation is far in excess of not only such theater, but also of the visual lexicon of the photojournalism that defined the war. Snows is perhaps better categorized amid “expanded cinema.” It was featured by Gene Youngblood in his book of that name as part of the experimentations with technology that effected not so much a sensory experience as a “process of becoming”— “like life,” as Youngblood would have it.¹⁹ Yet Snows escapes this categorization as well, not least due to Schneemann’s alarm at the purported innovations and liberating potential of new technologies of mass culture still contingent upon structures of control, especially in terms of gender and sexuality. She was not dedicated to expanding consciousness so much as to electrocuting it. Snows is less Living Theater, more theater of the undead.

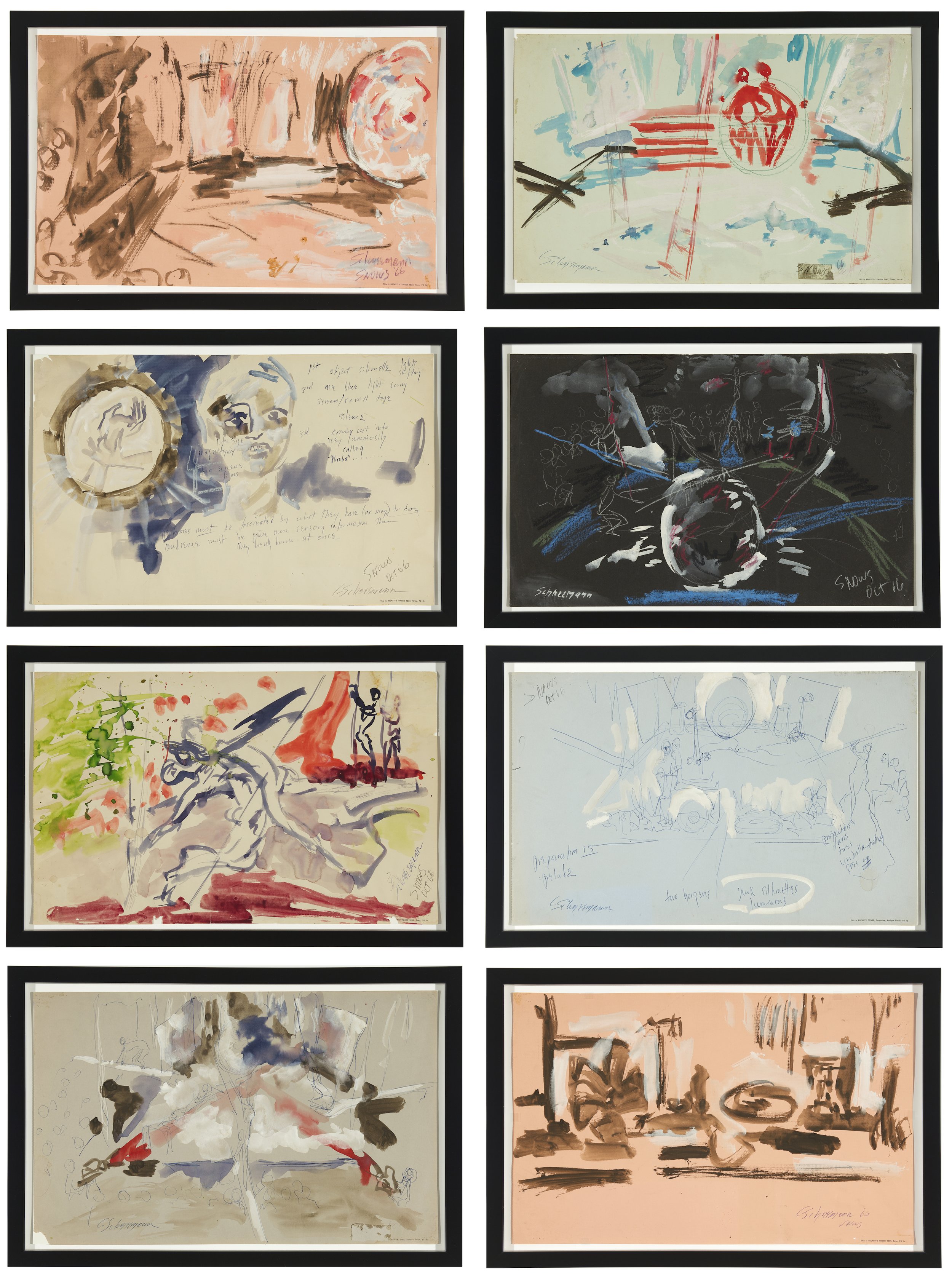

Images: Snows Drawings, 1966. Watercolor, crayon, and ink on paper. © Carolee Schneemann Foundation.

Snows is not a means to learn about the Vietnam War, but rather to learn what Schneemann’s mode of painting as collage can teach us about violence, power, and vision. Through a kind of collage in time—iterative not analogical, assemblage not synecdoche—she examines the antinomy of the snowflake to the avalanche, of Americana to its war machine. I propose that we shift the axis of the reception of Schneemann’s work from the famed Interior Scroll (1975/77) to Snows. This shift, from her notorious solo to a collaborative project incorporating avant-garde cinema, computer art and interactive systems, electronic music and expressionist theater, built in a context of anti-war protest, opens the rich opportunity to examine the confluence of a range of dynamic communities at the forefront of twentieth-century culture, and Schneemann’s participation in it, as terms of medium and media, process and performance, artist and audience were being redefined. Snows is a para-collage, a work of tearing, ripping, cutting, following precedents—from Dada to Fluxus to Nouveau Realisme—of manipulating qualities of positive and negative, values of light and dark, figure and ground, subject and object, working from the intrinsic condition of mass circulation to confuse space for time.²⁰ An electric shock crackles from Terminal Velocity (2001) and Dark Pond (2001–05) back to Tenebration (1961) straight through Snows, clarifying the parameters and politics of Schneemann’s work. This is how the coherence of Schneemann’s work reveals itself—in a blaze.

Schneemann claimed that she purposefully withheld from her collaborators that Snows was derived from Vietnam atrocity imagery. Though it is difficult to believe that this conceit could be maintained when we recall the prominence of Snows’ presentation in Angry Arts Week, we can deduce from her statement that there is an emphasis on displacing the referential capacity of the imagery. In seeming defiance of the very aims of protest art, the focus is not what an image tells us nor even shows, but on what it does to us.²¹ Consciousness is not raised; rather, it is snowed in. In the context of Libin’s program for Angry Arts Week, in which dozens of events were produced involving scores of participants at locations throughout Greenwich Village, Snows is a curious inclusion as much for its limited didactics as for its elaborate production. Snows holds the contradiction of joy and terror—this kinetic theater suspends disbelief in Troopers and audience, like the last creeping drifts in a snow globe, when its little world seems to stop, just before we shake it and shake it and shake it again. “Without [the performers] being aware of the central metaphor, the performance movements were able to evolve with spontaneity, suspense, immediacy, both directly and indirectly, from the related films and tapes,” Schneemann asserted.²² Snows derives its force from its exploration of how an image is made in the Vietnam War era, its exploration of the process by which the war took hold, one image after another, to become a national rite of passage, “constant as weather.” And in Snows we learn something of how America continues to revel in the images of the Vietnam War, atrocities and all—perhaps most of all—and how those images have become indelible to America’s stories about itself, the lessons of the devastation inflicted on the people of Southeast Asia never quite learned. Schneemann compels us to see how America is made in that violence, how America finds a particular kind of dark joy in its capacity for spectacular annihilation, how a kind of national character might even yearn and hunger for it. Through the “animal-intense” contortions of her Troopers, freezing themselves—ghastly friezes—and the Silver Walkers crushed in their paranoiac’s shells, Schneemann shows us how, at the end of the 1960s, America made its images, and was enveloped by them, amidst the media-machines of its savored delusions.

Christmas Eve, 1966: the headline accompanying Burchett’s photograph on the front page of the National Guardian reads “Vietnam: Insoluble U.S. crisis.” Insoluble: that which cannot be undone, or loosed, or solved. In Schneemann’s para-collages, we see her refusal, her no to the unitary masculine honorific, to the freeze: no rest, no merriment for gentlemen. Rather, darkness kept company. “The walkers are corpse-like, nearly unmovable. Together in a desperate struggle and clumsy haste they gather in a pile, collapsing under the film projection. The snow machine begins—snow falling, filling eyes and ears, covering all.”²³ This is how a body is made of pieces, how a body is torn. And this is how, image by image, rip by tear, the snow melts. So many images, so many fantasies stitched together in nerves and muscles. We see, we tear. “We set each other on fire, we create each other’s face and body, we abandon each other, we save each other, we take responsibility for each other, we lose responsibility for each other, we reveal each other, we choose, we respond, we build, we are destroyed.”²⁴

Notes

1. Project CHECO Southeast Asia Report: Rolling Thunder July 1965–December 1966 (Hickam Air Force Base, HI: Department of the Air Force, 1967), p. 126.

2. Wilfred Burchett was a regular contributor to the National Guardian, among other leftist publications. Burchett was acclaimed for his reports emerging from his extraordinary access to the People’s Army of Vietnam and Viet Cong forces. In 1978, Burchett provides his own, more expository caption for the photograph where he reprints it in his book Catapult to Freedom, now out of print: “The most common features at all schools [in North Vietnam], evacuated to the countryside, were the trench systems starting within the classroom and the stretchers for evacuating the wounded.” Wilfred Burchett, Catapult to Freedom (London: Quartet Books, 1978), p. vii.

3. Nick Turse, Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam (New York: Picador, 2013).

4. Carolee Schneemann, personal papers of the artist, accessed April 16, 2017.

5. Schneemann, “Snows,” in More Than Meat Joy: Complete Performance Works and Selected Writings, ed. Bruce McPherson (Kingston, NY: McPherson & Co., 1979/1997), p. 132.

6. Ibid., p. 130.

7. Ibid., p. 131.

8. Ibid., p. 134.

9. Carolee Schneemann, “Snows,” I-Kon 1, No. 5 (March 1968).

10. Schneemann, “Snows,” in More Than Meat Joy, pp. 131, 129.

11. Ibid., p. 134.

12. Ibid., p. 132.

13. See my Libidinal Engineers: three Studies in Cybernetics and Its Discontents, Chapter 3: “Meat System in Köln: Carolee Schneemann and the Electronic Activation Room,” PhD dissertation, Stanford University Department of Art and Art History, 2015, pp. 97–137, where I examine the coincidence between Schneemann’s use of human intrusion detectors in her work Meat System 1: Electronic Activation Room (1970) and the use of similar technologies by American armed forces under the name “Operation Igloo White” in their attempt to manage an “electronic battlefield” in Southeast Asia. More recently, Erica Levin describes this coincidence in her analysis of Snows in “To Change the Form of Film: Experiments in Cinema against the Television War,” in Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965–1975, pp. 305–24.

14. Schneemann, “Snows,” in More Than Meat Joy, p. 144.

15. Erica Levin analyzes Schneemann’s use of photographic war reportage in Snows and Viet-Flakes in the context of liberal discourses of anti–Vietnam War activism in “Sounding Snows: Bodily Static and the Politics of Visibility during the Vietnam War,” in Hybrid Aesthetics: Art in Collaboration with Science and Technology in the Long 1960s, ed. David Cateforis, Steven Duval and Shepherd Steiner (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018), pp. 113–24.

16. Schneemann, “Snows,” in More Than Meat Joy, p. 129.

17. Ibid.

18. Nick Turse, “A Mỹ Lai a Month,” The Nation, December 1, 2008. During the Mỹ Lai massacre of 1968, US troops slaughtered more than 500 civilians in Quang Ngai Province. In May 1970, a participant in the massacre wrote a confidential letter to William Westmoreland, Army chief of staff, saying that the Ninth division’s atrocities amounted to “a Mỹ Lai each month for over a year.”

19. Gene Youngblood, Expanded Cinema (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1970), p. 41.

20. In a longer study I elaborate on what I call “para-collage” in Schneemann’s work as it pertains to “dé-coll/age” as proposed by Wolf Vostell and other projects of Nouveau Realisme.

21. Schneemann, “Snows,” in More Than Meat Joy, p. 129–30.

22. Ibid., p. 130.

23. Ibid., p. 144.

24. Ibid., p. 132.