The New Television: Video After Television | Introduction by Tyler Maxin and Rebecca Cleman

EAI and no place press are thrilled to share an excerpt from The New Television: Video After Television. Our forthcoming two-part publication calls on voices across five decades of media and broadcasting, comprising a facsimile print of the foundational, yet understudied anthology The New Television: A Public/Private Art (1977) alongside new scholarly texts reflecting on video art from expanded contemporary perspectives.

Centerfold of The New Television: Video After Television (no place press, 2024). On the verso page is the cover of the The New Television: A Public/Private Art (1977), and on the recto page is the cover of the new publication.

The road to the publication of The New Television: A Public/Private Art in 1977 was winding. Designed and edited over a three-year period, the book is a compendium of papers written on the occasion of “Open Circuits: An International Conference on The Future of Television,” held in the trustee meeting room of the Museum of Modern Art in January 1974. Itself a long-delayed ordeal, the convening brought together many of the critical figures in what was beginning to be called “video art.” Over three afternoons, a mix of artists, gallerists, scholars, philosophers, and museum professionals discussed the emerging medium and what role institutions could play in supporting its development. The resulting meetings were more prosaic than the conference’s utopian organizers, who believed that television could unlock new possibilities for art and consciousness, initially had in mind. They had first conceived of “Open Circuits” as the sidebar of a grander project encompassing an internationally traveling exhibition, a video-viewing apparatus, and a television broadcast—none of which came to pass. All the same, the moment documented in this book represents a critical juncture for the meteoric development of media art, which was struggling to find a footing within museums, themselves undergoing rapid cultural change.

Fred Barzyk, “The Yin and Yang of It,” double-channel show broadcast simultaneously on WNET and WNEW, 1967.

The genesis of “Open Circuits” can be traced back roughly to 1968, when the artist and journalist Douglas Davis began to correspond with Fred Barzyk, a young producer at WGBH-TV in Boston.¹ WGBH was the first public television channel in New England (and one of the earliest in the United States), and its proximity to prestigious higher-education institutions gave it a particularly free-wheeling, intellectual bent, exemplified by such programs as Laboratory, which gave any station member the opportunity to pitch and execute an idea, and the pathbreaking lecture series Museum Open House (1963–67), a weekly gallery talk hosted by artist Russell Connor, broadcast live from the city’s Museum of Fine Arts.² Barzyk seized upon the station’s permissiveness by launching What’s Happening, Mr. Silver (1967–68), a weekly countercultural news program starring David Silver, a twenty-three-year-old literature professor at Tufts. The program often showcased frenetic interviews with guests such as Andy Warhol, the Velvet Underground, Bill Cosby, Mel Lyman and his Fort Hill Community, and John Cage, who performed a version of 4:33˝ on air.³ Barzyk would occasionally dedicate entire episodes to radical formal experiments such as “Madness and Intuition,” which was live-mixed according to motion-sensor inputs, and “The Double-Channel Experiment,” intended to be watched on two side-by-side televisions.

The program’s local notoriety quickly spawned national curiosity and blipped the radar of Douglas Davis, who was reviewing art and television in magazines, although his passion was reserved for the burgeoning field of art actions. With artists Juan Downey, Doug Michels, and Ed McGowin, he had helped found the New Group in Washington, DC, in the mid-’60s, whose “happenings” ranged from purposefully futile protests to experiments in behavioral feedback. United by their shared interest in the possibilities of television, Davis and Barzyk began to brainstorm a conference that would take the temperature of the artist’s television movement and advocate for opportunities and airtime.

Michael Shamberg, Raindance Corporation, Guerrilla Television (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971). Book designed by Ant Farm.

At the time of the pair’s meeting, the idea that American riffs on European avant-gardism (Fluxus, happenings, Minimalism, conceptually oriented for- malism) could be fused with the bête noire of television was unusual. Yet the following years would witness a number of important parallel developments. Owing to the introduction of consumer-grade video recording and playback (via the Sony DV-2400, developed in Japan in 1967), the goodwill of public and state-funded video channels, and the countercultural zeitgeist, a panoply of broadcast experiments and art-oriented televisual critical discourse began to crop up. In Cologne, Gerry Schum produced Fernsehgalerie (TV Gallery) (1967–70), which aired a documentary on Land art, an ambitious performance work by Aldo Tambellini and Otto Piene, and a televisual fireplace designed by Jan Tibbets. At San Francisco’s KQED, a group of artists and technologists opened the National Center for Experiments in Television (1969–74), a laboratory for audiovisual synthesis, while the art dealer and jazz aficionado Jim Newman commissioned long-form TV works by Anna Halprin, Terry Riley, Yvonne Rainer, and Walter De Maria on his Dilexi Series (1969–70). Bruce Nauman exhibited his video performances at the Nicholas Wilder Gallery in Los Angeles in 1968 and the Castelli Gallery in 1969. In New York City, video collectives such as the Raindance Corporation and Videofreex were sprouting up. The gallerist Howard Wise, who had built a reputation for exhibiting and supporting technology-based art by an important roster of artists including Hans Haacke, Marta Minujín, Bruno Munari, and Nam June Paik, hosted the catalytic TV as a Creative Medium (1969), often credited as the first exhibition in the United States to focus on how artists were working with television technology as a creative tool.

WGBH played an important role in this explosion of activity. In 1967, the Rockefeller Foundation awarded the station a three-year grant of $275,000 to establish an artist-in-residence program, the first of its kind for a television station, and between 1968 and 1969, Paik—the Korean-born artist and composer often cited as introducing the Sony portapak to New York artists— worked on the studio’s premises to experiment with its equipment and develop a video synthesizer. In 1969, the station aired The Medium Is the Medium, among the earliest examples of an American television studio directly commissioning visual artists’ interventions in the form. Aldo Tambellini presented Black for slides, film collage, and television sets, and Allan Kaprow staged Hello, which brought the camera into the studio control room and choreographed a chaotic live-feedback system. Otto Piene and James Seawright created image-processed modernist dance; Thomas Tadlock demonstrated his Archetron, a contraption using three monitors and mirrors outputting kaleidoscopic mandalas; and Paik collaged live-synthesized and appropriated images in his Electronic Opera #1, instructing viewers to close and open their eyes at various points in the broadcast.

The station’s boundary-pushing activities were seen as a model for other institutions looking to experiment with the medium. When the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) initiated a grant for artists working in video technology in 1971—the year consumer video cameras became more widely commercially available—it invited Connor and Barzyk to preside over the review panel. The pair’s experience and exposure to young artists working with video technology led them to develop The Very First Half-Inch Videotape Festival Ever (1972), the inaugural broadcast of portapak-shot material, circumventing the Federal Communications Commission’s restriction against consumer-grade footage by shooting it off monitors and showcasing emerging figures such as a young Bill Viola and the just-formed video collective Top Value Television (TVTV). New York’s PBS affiliate Thirteen/WNET modeled its own artist residency, TV Lab, which launched in 1972, after WGBH’s, with Paik and Barzyk advising on the Rockefeller Foundation– funded endeavor. Davis was in turn inspired by the activities at WGBH to lead Electronic Hokkadim (1971), a participatory broadcast on WTOP-TV in Washington, DC, which used the audio of live viewers’ phone calls to manipulate video synthesizers.

It was within this nascent ecosystem of artists’ television that Davis, Barzyk, and Connor began to shop the idea of an exhibition, conference, and catalogue to museums in the fall of 1970. The project’s name was borrowed from Paik’s 1966 aphorism “We are in open circuits” and initially clarified with the lofty subtitle “Art at the Beginning of the Electronic Age.” The proposal text was not subtle: “Open Circuits could affect the direction of art as profoundly as either the 1913 Armory show or Nine Evenings,” Davis wrote.⁴ In the original conception of the event, Barzyk was to oversee the production of an exhibition and screening program; Connor would choose videos; and Davis would supervise a conference, a “future room” (showing off new or speculative technology), and a live-event series including happenings by artists and collectives like Allan Kaprow, USCO, and Wolf Vostell. The trio would make decisions by majority vote and together produce a catalogue of newly commissioned texts. The project would explore such technological developments as “videofax publication of newspapers and magazines; wrap-around wall screens; live satellite TV pictures of the Earth on command; holographic TV projections into the viewer’s space; odors; TV touch systems (Video Braille); telecommand systems, linking viewer and com- puter to the complete videotape libraries; [and] 2-way TV system[s].”⁵ It would also feature a roster of experts and pundits weighing in on the medium—literary critic Lewis Mumford, Frankfurt School stalwart Herbert Marcuse, FCC chairman Nicholas Johnson, and media philosopher Marshall McLuhan, among others, were floated as possibilities.

Fred Barzyk, Douglas Davis, and Gerald O’Grady, exhibition proposal for Open Circuits: Art at the Beginning of the Electronic Age, 1972. Howard Wise Archives, Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York.

The Museum of Modern Art’s new director, John B. Hightower, was intrigued. The former head of NYSCA (and, incidentally, the boss of Davis’s wife, the critic Jane Bell Davis), Hightower had stepped into the position in early 1970 and circulated the proposal internally, praising it as a fascinating subject and claiming that “perhaps it will even persuade me to buy a television set!”⁶ MoMA film curator Willard Van Dyke responded enthusiastically: “This is one of those probing shows I believe we must do even though there are definite risks involved.”⁷ In early 1971, Hightower proposed a meeting with the group, suggesting that, “should we not be able to manufacture an exhibit with all the attendant hoopla, and fanfare—and expense—perhaps the conference idea could be worked out as an event of the MoMA Film Study Center,” and stipulated that the organizers fundraise for the project as an independent entity. Davis, for his part, secured financial backing from Electronic Arts Intermix, a budding nonprofit launched by Howard Wise. The museum promised it would offer assistance in the form of “letters, perhaps, and luncheons.”⁸

Hightower’s tenure at the museum would prove to be short-lived, however. He had inherited an institution with annual deficits of more than $1 million, and his folksy management style irked both the trustees, who found his populism and penchant for hearing out antiwar activists inelegant, and the staff, who were increasingly frustrated by the low wages and long hours. In August 1971, the Professional and Administrative Staff of the Museum of Modern Art—the first-ever union of museum professionals in the United States, formed just that year—went on strike, protesting a round of layoffs that included several bargaining-committee members. Hightower’s conciliatory response, which entertained the idea of adding artist representation to the board of trustees, infuriated his superiors (particularly the board’s chair, former CBS president William S. Paley), and he was fired at the end of the year. Richard Oldenburg, brother of artist Claes, was named as interim director, and the follow-up meetings with the conference organizers scheduled for that fall were canceled.

This behind-the-scenes tumult was the first of several stumbling blocks for “Open Circuits.” Determined to fundraise independently, Davis pounded the pavement, hiring Allison Simmons, a former classmate of his wife’s at Bennington and a secretary for Howard Wise, as a dedicated administrative assistant for the endeavor in spring 1972, and securing a NYSCA grant as well as funds from Wise. Davis also tapped the well of corporate philanthropy, which was just then emerging as an important constituent of arts funding (MoMA’s landmark 1970 Conceptual art exhibit Information, for example, had been underwritten by the Italian typewriter and computer manufacturer Olivetti). He reached out to Exxon, TV Guide, IBM, the CBS Foundation, and multiple Rockefeller funds. The applications were largely unsuccessful.

Oldenburg, presiding over an ailing institution that in 1972 was forced to cut its exhibition schedule in half in response to budget cuts, proved a far less sympathetic sponsor than Hightower. Van Dyke remained a champion of the project, as did Exhibitions Director Wilder Green, but the feasibility of the show came down to a question of space: A bid for use of the northeast gallery and auditorium lounge lost out to another exhibit, and the idea of installing it in the museum’s garden came to nothing. While Hightower had appeared enthusiastic about the commissioning of a catalogue, the publications department encouraged Davis to secure another publisher; the most they could do, in any case, would be to “place an order for a small number of copies to sell in our bookstore, and, of course, re-order should that prove necessary.”⁹ Davis shopped the book to Praeger, which had published his 1973 book Art and the Future, and the MIT Press, eventually choosing the latter owing to its penchant for forward-thinking design.

As the planning dragged on, the personnel changed. In the summer of 1972, Connor bowed out as co-organizer, owing to his appointment as a NYSCA officer specializing in television and media, and was replaced by Gerald O’Grady, a medieval scholar whose belief in the importance of “mediacy”—literacy in new technological forms—led him to found the SUNY Buffalo Center for Media Study around the same time. At one point that fall, Davis threatened to quit, feeling the strain of being the only New York City–based organizer and increasingly frustrated by criticism of his simultaneous role as art critic and video artist. The whole endeavor must have seemed largely hopeless at the beginning of 1973, with the group having filed two extensions on their NYSCA grant yet still having almost nothing to show for it. “Apparently the NYSCA report will state that MoMA—alone among museums in N.Y. state—reported no interest in video,” Davis wrote to Van Dyke that February. “This has left us all in a deeply embarrassing position.”¹⁰

O’Grady stewarded the final fundraising push that spring, galvanized by his experience at a small gathering of film and television professionals (including Barzyk, Jonas Mekas, and Steina Vasulka) organized by Van Dyke at the Mohonk Mountain House in New Paltz, which left him “with a feeling of very high hopes that something very important for all of us happened there.”¹¹ That June, the group was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts grant and given funds from the Rockefeller Foundation, bringing them to just $5,000 shy of the requisite budget for pulling off a pared-down realization of their project, a three-day conference on the state of television art. Davis and O’Grady went ahead and set the dates—January 23–25, 1974—and sent out panelist invitations in the fall.

“Open Circuits” conference schedule, January 23–24, 1974. Howard Wise Archives, Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York.

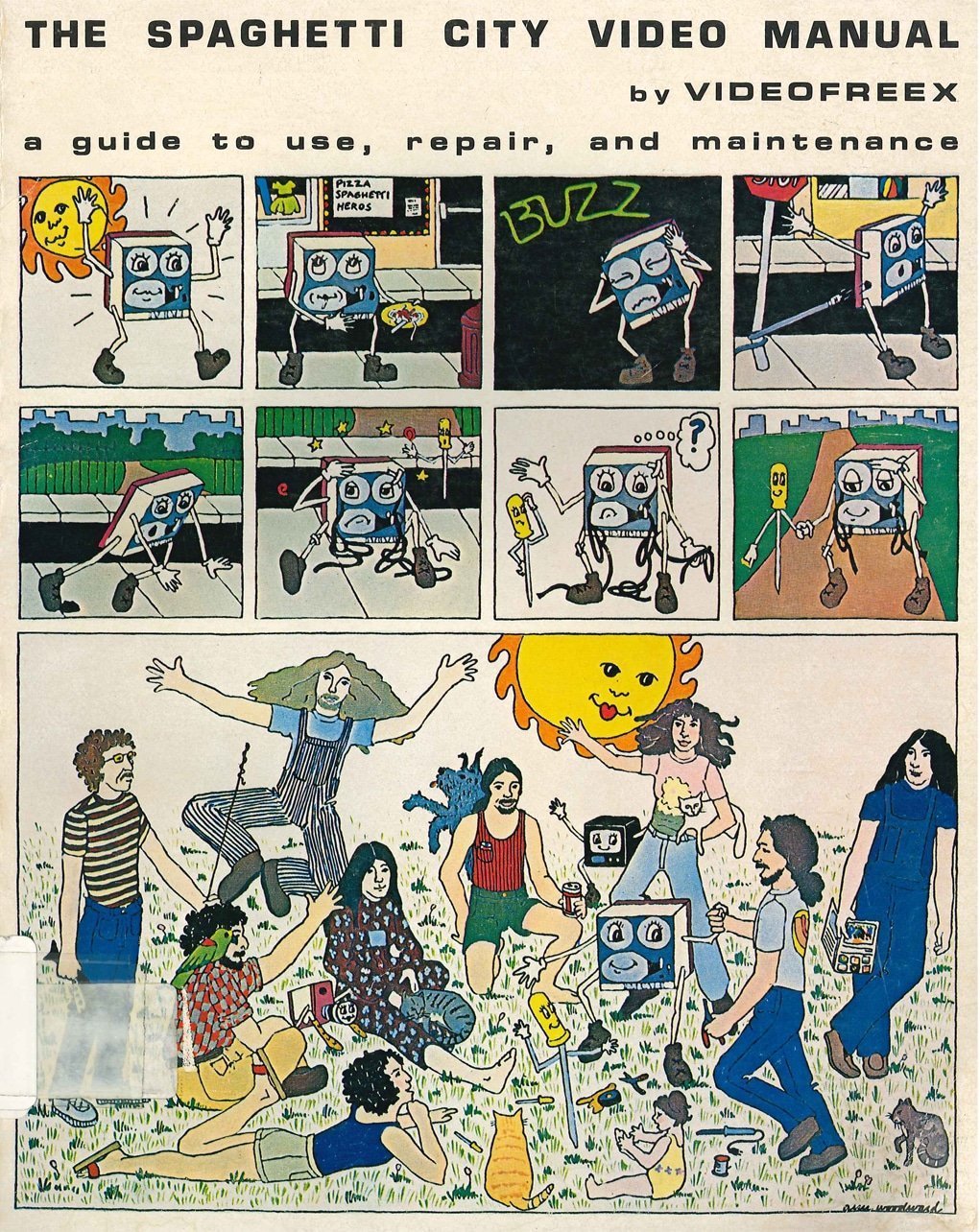

The eventual participants of “Open Circuits” were secured through a mixture of connections and circumstance, and the final roster was perhaps more a snapshot of video as an institutional network than the comprehensive reconsideration of a form Davis and company had envisioned. A lot had happened in the three years since their initial conversation with Hightower: Vision and Television, curated by Connor at Brandeis University’s Rose Art Museum in 1970, gathered works by members of Raindance, USCO, Global Village, and other groups; the Whitney presented A Special Videotape Show, a significant screening series taking the pulse of video synthesis, in 1971; and the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley assembled Tapes from All the Tribes, a cross-country selection of works by one hundred artists, that same year. The Walker Art Center hosted a National Video Festival, which included screenings, panels, and workshops. The Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse established the first-ever video division for an art museum, led by the young curator David Ross, and hosted an array of technically intensive shows, such as Douglas Davis: An Exhibition Inside and Outside the Museum and Nam June Paik in 1972 and Circuit: A Video Invitation, a traveling exhibition of sixty-five artists, in 1973–74. Raindance Corporation, playfully named after the think tank the RAND Corporation, published Guerrilla Television, a “meta manual” offering practical and ideological insights into how video could be used for radical ends, and Videofreex produced their own instructional guide. New institutions were popping up: Woody and Steina Vasulka were presenting near-nightly multimedia events at the Kitchen, Ralph and Sherry Miller Hocking’s Experimental Television Center was offering access to video synthesizers and other tools outside of Binghamton, and Howard Wise’s Electronic Arts Intermix was funding a panoply of video-related projects, including the construction of a low-cost editing studio and the launch of a distribution service. Portapak systems proliferated across the United States and Europe, primarily on college campuses and in cultural collectives, as a means for low-cost communication. The FCC developed guidelines for public-access cable. Weaving together these various threads—image processing, happenings, body art, media ecology, conceptualism, radical political formations, media policy—would be no small task.

The context may have changed but the organizational themes remained for the most part steady. On the first day, artists and arts administrators would gather to discuss the “structure of television” and survey the flourishing of experimental television centers in the United States and internationally, buttressed by presentations by synthesizer builder Stephen Beck of the National Center for Experiments in Television and Brazilian philosopher Vilém Flusser. Day two would be dedicated to the “aesthetics of television” and focus more narrowly on the medium’s art-historical context, opening with a paper about the placement of the TV set in the home by critic Gregory Battcock and followed by a host of artist talks by the likes of John Baldessari, Ed Emshwiller, Hollis Frampton, Joan Jonas, Shirley Clarke, Stan VanDerBeek, and Davis. The third and final day was dedicated to considerations of the “politics and philosophy of television.” German poet and theorist Hans Magnus Enzensberger, then in the midst of developing a general working theory of the “consciousness industry,” would deliver an appeal to television’s role in political liberation; critic Bruce Kurtz would give a report on the state of public funding for video art; Swiss curator René Berger was to consider the medium’s impact on the social function of myth; and British Pop artist John McHale would speculate on the future of TV. The whole affair would conclude with a panel of professionals and artists chaired by Van Dyke on video and the museum that would advocate for increased resources.

Though the proceedings included a survey of the emerging international video scene (at one point, Davis even dreamt of hosting a panel via satellite, connecting Cologne, Milan, and Tokyo), a panel on the subject seemed to conclude that this globality was still largely aspirational. Toshio Matsumoto admitted to being “perplexed by the fact that so many Americans assumed that video activities must be flourishing in Japan”; Argentine artist and curator Jorge Glusberg stated plainly that “in Latin America an art does not exist, but its impetus exists”; and Wolfgang Becker observed that across TV history, “European experiments have been dependent upon American models.”¹²

There were other shortcomings. Few of the collectives from the burgeoning alternative-media scene—Videofreex, the People’s Video Theater, Downtown Community TV Center—were represented in person, though video excerpts of their guerrilla activities were screened. Owing to budgetary and logistical constraints, the vast majority of conference participants were from New York State; only two, Beck and Baldessari, represented the nascent but rich West Coast video ecosystem, and Michael Snow was the sole Canadian invitee despite lively scenes at the Nova Scotia School of Art and Design and York University.

Videofreex, The Spaghetti City Video Manual (New York: Praeger, 1973).

A lack of gender diversity among the participants was also notable. Two weeks before the event, the artist and activist Jacqueline Skiles sent a scathing letter to Oldenburg, admonishing him for “permitting an activity which is clearly discriminating against women to take place on [the museum’s] premises.”¹³ This despite the fact that, thanks to its low cost and relative accessibility, video was an especially appealing medium to groups traditionally excluded by the film industry and corporate television, such as women, nonwhite, and queer artists. Shigeko Kubota did, however, manage in her contribution to review a bevy of activities by female video makers, including the formation of organizations such as the Women’s Video Festival and the Women’s Interart Center.

An atmosphere of anxiety permeated the planning of “Open Circuits” practically up until the day it began. In October 1973, MoMA staff organized a second, even larger strike, aiming to secure more robust contracts, union membership for full-time curators, and staff and artist representation on the board of trustees. The museum was picketed around the clock for nearly eight weeks. Davis and O’Grady, meanwhile, struggled to secure the last chunk of cash needed to make the conference happen, at first attempting to creatively cut costs. “Interestingly enough, it appears that Allison did not volunteer to give up two-thirds of her salary. Perhaps Gerry misunderstood her,” Davis wrote to Van Dyke just two weeks before the conference. “In any case, we absolutely must get $5,000 from somewhere.”¹⁴ Thanks to their dogged persistence, the CBS Foundation, which had initially rejected their inquiry, wrote a check at the eleventh hour for precisely that amount.

When it finally did come together, “Open Circuits” was held in front of a modest audience of around fifty panelists and artists, plus museum staff and invited guests such as PBS executive Chloe Aaron, former CBS president Frank Stanton, anthropologist Gregory Bateson, Center for Advanced Visual Studies founder György Kepes, documentary filmmaker Emile de Antonio, and underground-cinema maven Jonas Mekas. “Back then, MoMA had a much smaller footprint,” recalls Barbara London, a curator in the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books at the time, “and events like that took place in what was called the Founders Room, where trustee [and] big curatorial meetings were held.”¹⁵ According to London, at that moment the museum had no video equipment of its own, so the organizers had to wheel in monitors and hardware sourced from a rental house.

The atmosphere at the conference was variously intense and chaotic. Bill Viola, freshly graduated from Syracuse University, where he had co-founded the alternative-media collective Synapse and worked as a technician at the Everson Museum, remembers heated discussions going late into the night in rooms dense with a “sweaty, stale cigarette haze.”¹⁶ Gregory Battcock reportedly sent a surrogate, the Italian writer (and Lord of the Rings translator) Vittoria Alliata di Villafranca, in his stead, who claimed his identity for the duration of the conference and recited his essay “The Aesthetics of Boeing” in place of his scheduled keynote address.¹⁷ Davidson Gigliotti remembers that, following Hollis Frampton’s lecture “The Withering State of the Art,” Michael Snow stood up and delivered the same paper verbatim, presumably a gonzo comment on video playback.¹⁸ And Kubota reports that John McHale, who was supposed to present on the future of television, exited the proceedings out of boredom.¹⁹

Almost everyone who participated in the conference remembers the palpable tension that developed between the “technologist” or “synthesist” camp of abstract-video proselytizers, on the one hand, and the conceptualists, on the other, which threatened to hijack nearly every panel debate. The former encompassed both the formalism of Frank Gillette, who was using video abstraction to explore ecological systems, and Stephen Beck, a hippie-ish West Coaster who had developed one of the first audiovisual synthesizers, while the latter counted Robert Pincus-Witten, an Artforum critic and historian of Minimalism, and artist John Baldessari among its ranks. Pincus-Witten accused Gillette of being an “apologist for the separatist nature of technology,” claiming that the utopian rhetoric of video’s early adopters was undermined by its present clunkiness. The critic suggested that if the idealists wanted a democratic medium, they should look no further than a “Crayola box,” a statement echoed by Baldessari’s suggestion that video would only come into its own as a medium once it became as commonplace “as a pencil.”²⁰

Beck, meanwhile, became a lightning rod for criticism of psychedelic image-processing, which was losing its luster amid the general retreat of the countercultural verve of the ’60s. Pincus-Witten chastised feedback artists for relying on a dated “pictorialism” and on iconography borrowed from popular visual culture, implicitly jabbing at Beck’s use of geometric mandalas. As Beck recalls:

I remember Gerald O’Grady was sort of egging me on like a boxer to get on the floor and debate with these critics. [They had been making] negative comments about me and my work and the genre of video synthesizers saying, “Well, we’ve seen all this before, this is nothing new.” So my response was to take out a dollar bill from my pocket and light it on fire with a lighter. And then I stood on my head for five minutes while the bill slowly burned. They were astonished because these were verbal people—writers—and their domain was the written word. As art critics, they were writing words about things that were published in important journals or magazines, what have you. So to respond to that with a completely nonverbal stunt like that left them literally speechless.²¹

For many attendees, the standoff between Beck and Pincus-Witten became the symbolic crux of the conference.

“Rather than the starting point many felt it would be, ‘Open Circuits’ turned out to be a summing up,” reflected Howard Klein, the Rockefeller Foundation’s director of arts at the time of the conference.²² From 1969 to 1974, the foundation was the single most significant supporter of the experimental-television-studio model, incubating Boston’s WGBH, New York’s TV Lab at WNET, and the circuit of stations that grew out of San Francisco’s National Center for Experiments in Television, where Beck cut his teeth as its first artist-in-residence. According to Klein, despite the perceived success of this approach, a new funding model was on the horizon, one that prioritized media-research laboratories at universities rather than embedding artists in professional studio facilities. Indeed, over the following years, these programs slowly wound down: The NCET dissolved in 1975; WNET began to emphasize the weekly video-art showcase series Video Tape Review (VTR), hosted by Russell Connor, over its in-house residency; and at WGBH, Fred Barzyk shifted his energies to narrative works, including the ill-fated comedy Collisions (1977), which paired a science-fiction plot starring Lily Tomlin with interstitials by artists like William Wegman, and The Lathe of Heaven (1980), an adaptation of Ursula K. Le Guin’s novel with special effects by Ed Emshwiller. The heady dreams of consciousness-expanding national broadcasts were thus replaced by new hopes for cable-casting (especially local public access), satellite transmission, and consumer-grade video, which was increasing in capability and decreasing in cost by the year.

This shift had clearly been registered by Davis when he told an audience at a 1976 gathering of the American Association of Museums’ northeast section in Wilmington, Delaware, that he and Paik shared a belief that “a dollar devoted to [cable,] this exceedingly low-cost and time-rich medium[,] will produce many more hours of actual experiment (in terms of broadcasting) than a dollar flushed down the hideously expensive drain that is networks—and PBS, now itself a big business.”²³ Perhaps the most idealistic of the “Open Circuits” organizers, Davis had hoped that the conference would mobilize the museum’s resources to help artists navigate some of the obstacles they faced in getting their work shown. But in the AAM lecture his frustration is plain:

Time and again we urge upon major museums the use of television to exhibit our work, via free telecast, into the homes of an audience as large—at least in New York—as the museum visiting audience. Time and again the decision is to mount expensive, crowded displays of hardware in tiny quarters where the audience can barely move around, much less watch a videotape in focused silence.²⁴

Davis was far from the only “Open Circuits” participant to wax effusive about the possibilities that TV broadcast might offer institutions. Documenta 5 curator Harald Szeemann had anticipated that the figure of the “video curator” could “change the one-way system of production-reception into a triangle” and spoke hopefully of a speculative “creative distribution and production center” taking shape at the Centre Pompidou.²⁵ David Ross expounded on the “astonishing” curatorial possibilities that cable access could provide institutions and expected that “the museum will be in a position to use television channel time in the same way it utilizes gallery space within the museum’s building.”²⁶ But with occasional exceptions—like the Long Beach Museum of Art, which housed a TV production facility and an array of cable programs under the direction of Ross beginning in 1975, and the PBS-syndicated Alive from Off Center (1985–92), produced at the Walker Art Center—this concept did not often bear fruit in American museums.

Allan Kaprow, Hello, from The Medium Is the Medium, 1969, WGBH-TV.

“Open Circuits” did have a significant impact on its host institution: In 1974, MoMA founded its video program, steered by Barbara London. “When I got the grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to start ‘Video Viewpoints’ and to get myself out of the prints department, I [was going] out on a limb,” she recalls. “I didn’t know if MoMA would continue my salary.” She describes a museum culture that had up to then been characterized by a general dismissiveness and entrenched fear of technology, claiming she once overheard the head of the Department of Painting and Sculpture say he was glad London had taken on the project because it kept his curators away from video. In September 1974, the museum introduced a series of video exhibitions on a pair of monitors near its film auditorium, rotating looping thematic programs that surveyed topics such as American video performance, European Conceptual art, and documentary. As for why the museum didn’t embrace a production or broadcast model, London states simply that MoMA “would never have a studio because it never produces artwork in any medium. It never supports the production of artwork, except [to] give material fees to artists creating a new installation.”²⁷

And so it is an instructive irony that the ideas shared in “Open Circuits” slowly became accessible to a broader audience by way not of a TV broadcast or videotape but a good, old-fashioned book. The New Television, for its part, captured this transitional moment in museum culture with vivid frankness, communicating the era’s mixed signals through its structure and layout. In the three years following “Open Circuits,” Davis and Simmons gathered submitted papers (including those that apparently went unread, like McHale’s), transcribed panel exchanges, and collected post-conference reflections and other relevant material (such as Liza Béar’s interview with Richard Serra, originally published in Avalanche, and Connor’s consideration of artists’ cable video from The AFI Report). They also commissioned new essays: Simmons’s introduction, glossing the history of art and television’s entanglement; London’s summary of the early days of the MoMA video program; and Klein’s elegy for “televangelists” like Beck and Barzyk.

The book’s structure and design were an antic hodge-podge. Typefaces, font size, and text placement vary playfully, in the style of counterculture publications of the day such as McLuhan and Fiore’s The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects (1967). Most striking of all was the decision to preserve Simmons’s handwritten copyedits throughout. According to Simmons, Davis had wanted the book’s design to be “immediate and unvarnished and not prepackaged and smoothed over”;²⁸ they hoped thereby to bottle some of the unfettered immediacy of a guerrilla broadcast. Reviewing the book for the journal Leonardo, Ray E. Knight suggested that its design elicited “a feeling that one is witnessing the book in its making” while also serving as a reminder of “how accessible video ought to be but often is not.”²⁹

Though Knight’s review—one of just a handful, published primarily in academic journals such as ARLIS/ NA and The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism—is ultimately positive, he concludes with a paraphrase of Pincus-Witten’s claim that “nothing in modern culture dates more rapidly than technology,” a wry suggestion that the collection’s content was already starting to wear. In the relatively brief interim between conference and publication, video technology and artists’ corresponding responses were developing rapidly, from the introduction of the VHS tape in 1976 to early experiments with satellite connectivity via Davis, Paik, and Joseph Beuys’s documenta 6 broadcast, Liza Béar and Keith Sonnier’s Send/Receive Satellite Network, and Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz’s satellite experiments, all in 1977. Even the book’s cover—a matter-of-fact listing of the contributors with soft scan lines indicative of a screen—might have seemed dated in the context of the Pictures Generation and New Wave, whose practitioners were an emerging younger generation of baby boomers who had grown up with TV.

But while The New Television was marked by the conventions of its time, many of its themes continue to remain vital. Across the papers and talks, which variously discussed the nature of viewership, the politics of video, the prospects of cable and global connectivity, and the how and why of artists’ interventions in these technologies, the question of access almost always looms. Who could create images, and who could then see them? Or, better yet, who has the ability to intervene in them? In museums during the 1960s and ’70s, there was a flurry of conversations addressing gender and racial diversity in exhibitions and collections, the ostensible anti-populism of contemporary art, and the inappropriate control wielded by wealthy trustees over programming and administrative decisions. Artists sought alternatives to the unidirectional dynamics of television and museums both, looking towards interactivity, tape-swapping networks, local cable-casting, guerrilla documentation, and other strategies of media dissent, with hopes of radically changing the parameters of these systems. This dream triumphed, in certain respects: Today’s media environment is rich in choice, connectivity, participation, and immediacy. But in other ways, the questions opened up in “Open Circuits” remain active, as artists and thinkers continue to grapple with the realities of corporate-driven media platforms and art institutions in crises. Returning to The New Television a half-century later, readers can catch glimpses of alternate imaginations, utopias foreclosed, and debates ongoing of what media could do, a potent reminder of the fundamental structures and possibilities of a technology now nearly taken for granted in its ubiquity.

Notes

1. Originally trained in theater, Barzyk had come to Boston in 1958 to pursue a master’s in communications, which included a work-study component at WGBH as part of its scholarship package. The television station was an outgrowth of the public FM band of the same name and used equipment from the nearby Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1960, Barzyk wrote and directed his own broadcast, an experimen- tal, Brechtian antiwar play called Five Days, using a bare-bones soundstage. The following year, he began to surreptitiously commandeer studio equipment to record Jazz Images (started in 1961 and aired in 1964), a proto-psychedelic montage that curator Barbara London describes as “one of the first attempts at experimental television.” See Barbara London, “Video: A Selected Chronology, 1963–1983,” Art Journal 45, no. 3 (Fall 1985).

2. One highlight was a conversation between Connor and Marcel Duchamp broadcast in 1964, an early American appearance by the artist, who was in town on the occasion of an exhibition of his brother Jacques Villon’s work at the museum.

3. Ryan H. Walsh, “Boston’s Most Radical TV Show Blew the Minds of a Stoned Generation in 1967,” Boston Globe, March 1, 2018.

4. Douglas Davis, letter to John Hightower, October 5, 1970. All letters from Film Archives, the Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.

5. Douglas Davis, Fred Barzyk, and Russell Connor, “Open Circuits: Statement of Purpose,” circa 1971–72.

6. John Hightower, letter to Wilder Green, October 28, 1970.

7. Willard Van Dyke, letter to John B. Hightower, January 25, 1971.

8. Douglas Davis, letter to John B. Hightower, July 23, 1971.

9. Carl Morse, letter to Allison Simmons, October 24, 1973.

10. Douglas Davis, letter to Willard Van Dyke, February 21, 1973.

11. Gerald O’Grady, letter to Willard Van Dyke, February 19, 1973.

12. Comments printed in The New Television: A Public Private Art, ed. Douglas Davis and Allison Simmons (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1977), 195, 203, and 192, respectively.

13. Jacqueline Skiles, letter to Richard Oldenburg, January 4, 1974. For further discussion and the full letter, see Helena Shaskevich, “We Were Here All Along,” in this volume.

14. Douglas Davis, letter to Willard Van Dyke, January 15, 1974.

15. Conversation with the authors, December 13, 2022.

16. Bill Viola, “The European Scene and Other Observations,” in Video Art: An Anthology, ed. Beryl Korot and Ira Schneider (New York: Harcourt, 1976).

17. Douglas Davis, “Gregory Battcock,” Artforum, April 1981.

18. Davidson Gigliotti, “The Annotated Video Exhibition List (1963–1975),” davidsonsfiles.org/ Exhibitions.html.

19. See Shigeko Kubota, “Video—Open Circuits,” and Howard Klein, “The Rise of the Televisualists,” in The New Television, 158. Reprinted in this volume.

20. John Baldessari, “TV (1) Is Like a Pencil and (2) Won’t Bite Your Leg,” in The New Television, 110. Reprinted in this volume.

21. Conversation with the authors, November 17, 2022.

22. Klein, “The Rise of the Televisualists,” 158.

23. Douglas Davis, “The Decline and Fall of Pop,” in Artculture: Essays on the Postmodern (New York: Harper and Row, 1977), 86.

24. Ibid., 90–91.

25. Harald Szeemann, “Video, Myths, and the Museum,” in The New Television, 137. Reprinted in this volume.

26. David Ross, “Video and the Future of the Museum,” in The New Television, 115. Reprinted in this volume.

27. Conversation with authors, December 13, 2022.

28. Conversation with authors, November 18, 2022.

29. Ray E. Knight, “Review of The New Television: A Public/Private Art,” Leonardo 11, no. 3 (1978): 255–56.